Chapter Four

South West Africa, Far From Home

On our return to Elandsfontein on 18 December, we busied ourselves with getting our kit in order and packed, and on either the 20th or 21st (I forget which day) we were all assembled in dress uniforms and taken to Services School with all of our kit. Here we were issued with our rail warrants and then taken to Pretoria Station to catch the civilian train going to Windhoek. I remember that we were excited rather than depressed, as we were not being escorted by any one of rank, and thus had the run of the train to ourselves, or so we thought.

The trip itself was also to be a long one, three and a half days, as the train first headed for Cape Town, stopping at the marshalling yards in de Aar, in the central Cape Province. Here the coaches going to Windhoek would be uncoupled and attached to the Windhoek train, which travelled up from Cape Town to Windhoek.

Once the train set off we were like a bunch of school kids, and bottles of smuggled alcohol quickly appeared, to be consumed by all, while uniforms were discarded and civvies put on in their place. I had never been on a long train journey, so was quite excited at the prospect. It proved to be a mixture of both excitement and sheer boredom, mixed with bouts of misbehaviour in equal share. I think the conductor in our particular coach was a saint as, placed in his shoes, I would have evicted all of us from the train! Older heads are more understanding I suppose, and he knew where we were going. All he did was read us the riot act from time to time, and check up on us regularly so that we were never quite sure if he was around to catch us misbehaving.

We slept about four to a cabin, on bunks, and I got the top bunk. This made it awkward if you needed a comfort stop in the night, as you had to climb down carefully past the two bunks below you. The other bunk was on the opposite side of the cabin. The upside was that you were above any shenanigans going on in the cabin, a fact I was to be grateful for more than a year later, during my train journey back to South Africa.

Three and a half dusty days and nights on the train, during which I had enjoyed the changing scenery until we crossed into the Northern Cape and then South West Africa itself. where it gradually became drab and desert like, came to an end in the early morning on Christmas Eve 1978, when we pulled into Windhoek central station. It was a sunny but cool morning, and that wasn't the only surprise we received. We disembarked with all of our kit, and eventually found transport to the main base camp, where the men stationed in Windhoek slept and ate. This was a collection of a few PF houses, a medical centre, toilet and shower block, parade ground and a large area filled with tents in neat rows, plus a kitchen and two mess halls, the latter all attached to one another, where the other ranks and NCO's ate. What the base was called I no longer remember, but first impressions were not favourable. It was a dust bowl, with little to commend it, and we all couldn't wait to get away from it.

Here we tried to find someone who knew about us, and our transport requirements to Grootfontein, but to our annoyance, nobody seemed to have heard of us or know why we were there! I was still naïve enough to believe that the army cared about our ultimate welfare, so was very frustrated by the delay, and will admit to some very uncharitable thoughts about them just then. After much pleading of our case, we were grudgingly given a blanket each from the stores, with the admonishment that it had better be returned, and told to go and `find an empty tent' ! This we did, and I moved into one such tent with the man with the pregnant girlfriend, and two or three others. The tents themselves were bare, except for iron beds with foam mattresses, and we were expected to sleep on these with just the blanket until someone could think of what to do with us.

The latter wasn't going to be a problem though, as by now it was midday, and the temperature was in the 30s (degrees Centigrade). We sweltered as we were unused to such hot temperatures, and my friend with the pregnant girlfriend, plus another Portuguese friend Tony Pereira, went for a walk in the city centre, which although not close, was within walking distance.

We found the place to be crawling with infantry officers and NCO's, all obviously newly qualified from the Infantry School at Oudtshoorn and now headed for parts north, like us. They were a jumped up group too, having only newly been promoted, and there was much saluting and strekking going on between them. I may explain here that strekking was something you did when you passed by an NCO or Warrant Officer. It was done by placing your arms stiffly by your side as you walked, and greeting the NCO, who would return the greeting.

Officers we were required to salute, and one of these infantry 2nd Lieutenants took exception to the three of us as we walked right by him without giving him the time of day, never mind a salute. By now we were a little older and wiser, if you could call an 18 year old that, and we reasoned that the Lieutenant wasn't in charge of us and we didn't need to acknowledge his existence. He must have been most offended by these upstarts in blue berets, and he screamed at us to halt and come back, but only Tony obeyed. The other man and I just pretended we hadn't heard him and kept walking! Poor Tony copped the brunt of the Lieutenant's anger, being made to march back and forth in front of the latter, saluting the whole while, before being sent on his way with a veiled threat hanging over him. This all happened in Kaiserstrasse too, the main road in central Windhoek, and all the civvies just starred at poor Tony as he marched back and forth. I had great fun laughing at him afterwards, although he failed to see the funny side of it and kept calling us bastards for leaving him at the Lieutenant's mercy.

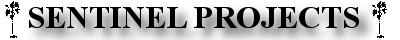

A map of South West Africa, now the independent country of Namibia, showing all the major and minor towns mentioned in this book.

The following day was Christmas Day, and was even hotter than the day before. There was a large water tank at the base camp, and we discovered that all the National Servicemen still in town were using it to swim in, as a way of cooling off. I joined in, and later we were all allowed to partake of Christmas dinner, served in the mess at the midday meal. This was a most sumptuous affair, with everything, including glazed pig heads and trifle, and we ate until we felt as if we would burst.

Boxing Day came and went, and at last on Wednesday 27 December most of the PF's in Windhoek returned to work, and we were told to prepare to be transported further north. Before we could move though, the Staff Sergeant in charge of the kitchen at the base camp, having heard of our arrival, ordered us to report to the mess. Being still very much roofs and not quite sure what to make of this order, we all complied, and I have wanted to kick myself ever since!

We trooped into the mess like sheep, to be greeted by the two Staff Sergeants and a Corporal, who proceeded to tell us that they needed about eight of us in Windhoek, to replace men who were nearing the end of their two year National Service, and would select the unfortunate few from among our ranks. Before any of us could protest, the Staff Sergeant in charge and the Corporal picked a few of us from the group and ordered us to stay behind, dismissing the rest. I was picked out by the Staff, and to this day I can hear his words, "Jy lange!" (you, tall one!). I cursed my height once again, something I had done since primary school as it always seemed to make me be noticeable at the wrong times, and stayed behind with the rest who had been chosen to stay in Windhoek. We were now under the control of South West Africa Command.

My mood was very black and depressed. Now, not only was I too far away from home to get there on anything other than a week long leave pass, but now I wasn't even going to an operational or semi-operational area. I was still young and foolish enough to think that the latter was a better plan than staying safe and sound in Windhoek.

South West Africa Command: Windhoek

The Staff in charge introduced himself as Staff Sergeant de Souza, and then sent us off with the Corporal, Egon von Bentheim, to get our local kit issued and accommodation sorted out. The latter turned out to be a tent, complete with iron beds and foam mattresses, standing on its own some distance behind the kitchens, and nowhere near the rest of the tents in the camp. This was necessary as we worked odd hours as chefs and woke very early or came to bed quite late, depending what shift we worked.

The kit issue was chef whites, which we were supposed to wear when working in the kitchens, but they didn't have any to fit me, and I always wore my normal nutria browns, as did a number of the other chefs.

Much to our surprise we were informed that, even in Windhoek, we were considered to be in a semi-operational area, and were issued with rifles with two full 20-round magazines of 7.62 mm ammunition. The rifles were new to us, G.3s, which I understand the Portuguese used in Angola and Mozambique, when they were still Portuguese colonies. We very quickly discovered that the G.3, although a good rifle generally, had one serious flaw. The stock cover over the barrel had no air holes in it, and there was a metal plate inside this that would get very hot very quickly when the rifle was fired, making it difficult to hold as it burned your hand! I was never to use mine in anger, as you would expect to be the case for a chef, but did have occasion to carry it around, cocked and ready, later.

The G.3 Rifle

My disappointment at being held back in Windhoek was eased somewhat by finding two men there that I had known at school. The latter were an old school friend of my brother's, Dennis Adeline, who was a National Serviceman in the SAAF and had already been in Windhoek for about three months by the time I arrived, and Graham Dickson, a dog handler in the army, whom I had played rugby with at Forest High School some three years before. Graham had been in Windhoek for two months. I wasn't to form long or lasting friendships with either, but it was great to see familiar faces other than my fellow chefs, especially at the start, and I spent a lot of time in Graham's company particularly.

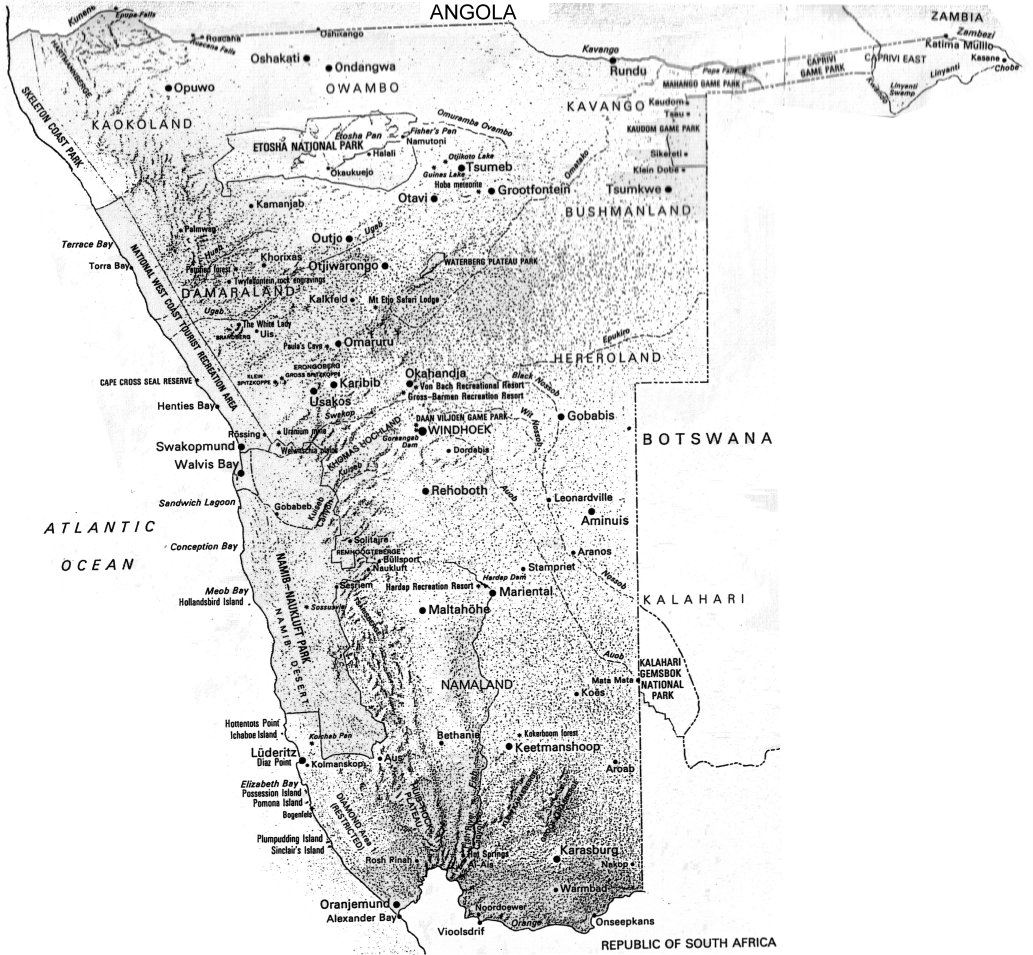

At the base camp kitchen we were introduced to the routine, and gradually got to know the men already working there. These were a mixture of PF's and National Servicemen, and a very odd lot indeed. In charge was Staff Sergeant de Souza, a short man with glasses, who had a fiery temper at times and was inclined to sit on his backside in the office, and leave everyone else to do the work. He lived on the base, in one of the PF houses, with his wife and kids.

His second in command was another Staff Sergeant, Lourens, also a married PF who lived off base. Lourens was a gentler soul, although he could be as fierce as the rest when needed. He had an absolute tart for a wife, a pretty young woman whom I understood to be the daughter of some other high ranking PF in Pretoria. This woman whored around the base with a number of other men, and was a constant source of embarrassment to Staff Sergeant Lourens. They had evidently married very young, and by the time I got to know him, they were in their mid twenties but had four young children already. I think his wife just flipped out and rebelled at her dreary life, and started screwing around.

I came to be quite friendly with Staff Lourens while I was stationed in Windhoek, and felt very sorry for him. He had the saddest eyes I ever saw in any man, and my one photo of him shows this nicely. One night, after we had finished up in the kitchen, I walked home with him to his house, at his invitation. When we arrived there it was already dark, but all the lights in the house were off, despite the fact that he was expecting to find his wife and kids at home. We went in, to discover all the children scrabbling around in the dark, in various dirty states, as small children do get, and their mother nowhere to be seen. She had gone out with one of her men friends again and just left the kids to their own devices. A couple had soiled themselves and it was just lucky that they were too small to do much damage to themselves in the time they were alone. The Staff busied himself with attending to the children, all the while apologising to me, and I made an awkward and hasty exit, mumbling some excuse about having to get back to the camp before my absence was discovered, as I was out without permission. I was so embarrassed, more for Staff Lourens than myself. I think the saddest thing was that his shoulders just went down that little bit more, yet he said nothing to his wife. Around her he was like a beaten dog.

After I had already left South West Africa, I believe the Army put their foot down and called both in and read them the riot act, insisting that she behave herself and that he take her in hand. Then they transferred both to a camp in the operational area, right on the border. This is what I heard anyway.

Staff Sergeant Lourens, chopping meat in the base kitchen in Windhoek.

Mrs Lourens' boyfriend of the moment when I arrived in Windhoek was a Navy Leading Seaman, or Killick, who also worked in the kitchen. How a navy man came to be working in an army kitchen I never found out, and he wasn't the only one I was to encounter while in Windhoek. Anyway, he wasn't there long as the situation was clearly untenable with him and Staff Lourens working in the same kitchen and he having sex with Staff Lourens' wife. The Killick was quickly transferred elsewhere, I think at the instigation of Staff de Souza.

There were three resident Corporals, two PF and one National Serviceman. The former were Corporal Cees van Helden and Corporal Venter, and the latter was Egon von Bentheim. All were Afrikaans, although van Helden's ancestry was Dutch. He was quite fierce at first, but became a firm mate later on. He was married to Lizette, a former army nurse whom he had met while in hospital some year or two before. She was a very plain looking girl but had the kindest heart one could hope to meet. Nothing was too much trouble for her, and the two of them made a lovely couple.

Corporal Venter was gay, which always amused us National Servicemen as openly gay people were not allowed to serve in the South African army. He was always immaculately groomed, and spoke with an affected air and drove an e-type Jaguar, which was his pride and joy. To be honest, he never attempted to hit on any of us, although he did take up with a young National Serviceman later that year, for which I understand he received a severe censure! This was again after my time in Windhoek though.

Corporal von Bentheim was a local man, from Mariental, south of Windhoek, and was quite a flamboyant character. He too was always immaculately dressed in white, and looked upon being a chef as the pinnacle of achievement, whereas the rest of us were chefs by force, not choice. I see today (2006) that there is an Egon von Bentheim who is a highly regarded member of the Namibian Chef's Association, so perhaps the Egon that I knew went on to greater things. He never completed his two year National Service, somehow managing to get himself discharged about four months early, and only about two months after I arrived at the base kitchen.

The last NCO whose name I can still recall was Lance Corporal Steyn, another National Serviceman who was quite a friendly but simple fellow. I found him easy to put off his stride, and didn't really look upon him as being my superior in rank, only when it suited my purpose, e.g. if I wanted someone to sign a leave pass so that I could go into the city centre. On the other hand, he was not nearly as full of crap as the other Corporals, and was inclined to hang out with the Privates rather than the other NCOs.

Besides these NCOs, there were only a couple of Privates like us new men, and the kitchen ranks were decidedly `top heavy' before we arrived! One of the `ou manne' was also a local English speaking lad, from Windhoek itself. I remember that he klaared out in July 1979, but don't remember his name.

Corporal Venter (left) and Lance Corporal Steyn (right).

Routine in South West Africa Command

Once settled in, we were quickly appraised of the routine that prevailed at the base camp kitchen. The chefs worked permanent shifts, and if rostered to make breakfast, your day began at about 3.30 am, an ungodly hour at best! This was when you woke and did your shaving, washing etc. before reporting in the kitchen at 4.30 am. What amused me was that no PF's ever turned up at that time, and breakfast preparation was almost entirely done by us National Servicemen, the PF's only showed up for work at about 6 am, just before you were ready to serve breakfast.

The back of the kitchen at the base camp in Windhoek. The E-type Jaguar parked on the left belonged to Corporal Venter, and it was his pride and joy.

Menus were done by the Staff Sergeant in charge, in this case de Souza, and he decided what each day's meals would be, usually in advance so that he didn't have to turn up for work until well after breakfast!

In Windhoek food was plentiful and the men ate well generally, and this included breakfast. The latter could comprise of eggs of various kinds (boiled, scrambled or fried), cereals, toast or bread, orange juice, coffee and sometimes even sausages. It took us all of the two and a half hours before breakfast started, which was at 6.30 am, to get the breakfast cooked, as we not only cooked for the men at the base camp, but those on duty at outlying posts around the city.

There were a lot of stations around the city and its environs, including engineer workshops, where vehicles were repaired. The Eros airport was another military facility, being staffed mainly by SAAF guys but with a smattering of army signallers and clerks around to run things. The main headquarters of South West Africa Command was in a large multi-story building in the city centre, known as the Bastion, and there were also a few guards scattered around at sensitive civilian and military installations, like power stations, and also at Major General Jannie Geldenhuys' private residence. He was the officer commanding SWA Command, and his house was guarded night and day by the infantry dog handlers. My friend Graham Dickson did most of his duty here.

The main street in Windhoek city centre, Kaiserstrasse.

All of the men at all these outlying posts took meal breaks, and travelled to the base camp to get their meals, but the sentries and signallers had no way of getting to the mess for meals when on duty, and we had to drive the meals out to them. For this purpose we had a duty driver attached to the kitchen at all times. His tasks included the fetching of supplies and the distribution of rations to these outlying posts. I often volunteered to accompany the driver, as this gave us a break from the kitchen and allowed us to see something of the city and its surrounds.

The food for these men was stored in metal containers after preparation, and the driver and chef went out on their rounds before the same meal was served at the mess itself. The food was always hot to start off with, but it was a long drive to get around to all the different guards, and took over an hour and a half to complete, by which stage the last few stops received cold food, poor bastards. They couldn't reheat it either, as this was all in the days before microwave ovens. The men would often not bother if the food was cold, merely helping themselves to generous amounts of bread, which we always took along with us.

My first few trips with the kitchen duty driver were interesting. He was a grizzled `ou man' with just under six months to go before he finished his two year National Service, and he had little or no military discipline, and it was quite an education for a roof like me to see how much disdain he treated the PFs with. I can't remember his name now, but he was a particularly keen Citizen Band (CB) radio enthusiast, which was the latest fad at the time. He used to bring his CB radio with him and just install it into whichever vehicle he was issued at the vehicle park, and spent the entire trip trying to chat up female CB radio hams, or talking to long distance truckies.

To get back to our routine though, once breakfast was finished for the day there was the big clean up, and then the same shift started the preparations for lunch. The kitchen had a lot of black civilian kitchen hands, who cleaned the kitchen and washed pots and pans, as well as peeled vegetables and potatoes, leaving the food preparation to us chefs. The kitchen hands weren't allowed to handle the meat however, and this was something we did from start to finish, butchering carcasses and cooking the meat in whatever form it was required for a particular meal. We National Servicemen also had to help with the cleaning, and occasionally the peeling, but our main task was to cook, under the direction of our NCOs.

The inside of the kitchen, with the gas stoves and ovens on the left, and a meat saw just visible on the right. The building visible through the windows was the other ranks mess. They entered it via the door in the centre of the picture, and were then fed by the chefs through an open section between their mess and the kitchen.

The rule that seemed to be in force at Base camp was that nobody above Corporal actually did much work, with Staff de Souza and his fellow NCOs congregating in the Staff's office, where they talked and drank coffee all day. Staff Lourens was probably most hard working senior NCO, as he would often cut up meat for us, using the butchery saw, or at least come out and see that we were doing our jobs properly.

Lunch was served at about 12.30 pm as I recall, and followed the same pattern as all meals; one of us went out with the driver to deliver food to the sentries around the city and environs, while the rest of us served the food we had cooked to the men coming in to eat at the mess from these same locations.

At the end of lunch, we again cleaned up, and then handed over to the new incoming shift at about 2 pm. Once we had done so, and been dismissed, we had the rest of the day off to do our own thing, although all this meant in reality was catch up on sleep (we had been up since 3.20 am, after all!), or do the many housekeeping chores we had like washing our dirty uniforms or cleaning gear and boots. It was usually too hot in summer to sleep, and I used the time to do my washing and write letters home.

The shift that cooked dinner finished in the kitchen at about 7.30 pm, but were then required to cook breakfast and lunch the following day too. This meant that you had a maximum of eight and a half hours between your shifts, during which you were expected to do your normal daily tasks and sleep. In the case of the shift that had been off the previous afternoon, they had the next morning off too, and started just after lunch.

By far the most punishing though were weekends. We would get every second weekend off, but this meant that the shift who were on duty had to cover the whole day, every day, from 4.30 am until 7 pm. On the weekends we worked, I usually used what little spare time we had to sleep, and wrote letters only to my fiancee Sharon then.

To summarise, the roster would have looked something like this:

WEEK ONE

| Sunday |

Monday |

Tuesday |

Wednesday |

Thursday |

Friday |

Saturday |

|

04:30 - 19:30 |

04:30 - 14:00 |

14:00 - 19:30 |

04:30 - 14:00 |

14:00 - 19:30 |

04:30 - 14:00 |

Weekend off |

WEEK TWO

| Sunday |

Monday |

Tuesday |

Wednesday |

Thursday |

Friday |

Saturday |

|

Weekend off |

14:00 - 19:30 |

04:30 - 14:00 |

14:00 - 19:30 |

04:30 - 14:00 |

14:00 - 19:30 |

04:30 - 19:30 |

and back round to week one.

In my entire National Service, I found every camp operated this shift pattern, and although it sounds exhausting at times, I got used to it very quickly. Besides, there were a number of obvious advantages to being a chef, and it wasn't just because of the easy access to food! Because we worked weird hours, we were not required to stand weekly inspections, which were still carried out at South West Africa Command. This meant even the guys who were not on duty on Friday mornings, when the inspections were generally held.

Easy access to food, in fact, was a distinct disadvantage in my case, as I grew to hate the stuff. Working with it all day very quickly put me off, and when I was first in Windhoek I started the rather unhealthy habit of eating cans of evaporated milk only, pilfered from the kitchen stores, which caused me a few bowel problems. The local medic doctor told me that I was damaging the lining of my stomach by drinking only the highly concentrated milk, and once I stopped doing so my ailment subsided, never to return. Throughout my service, and despite the excellent meals we sometimes cooked, I resorted to living off the most weird and wonderful foods at times, rather than eat what we had cooked for any particular meal. For example, I hated cabbage as a child, but took to eating plate loads of the stuff, spiced up with pepper, and nothing else. All of us used to make toasted cheese sandwiches too, using the hot plates on the kitchen stoves.

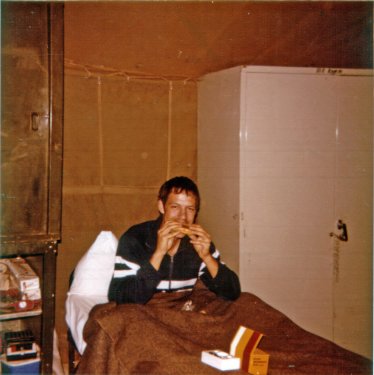

Eating a toasted sandwich in bed, in our tent, which was located some 20 yards behind the kitchen.

Another advantage to being a chef was that you never stood guard duty, for what I think are obvious reasons. The only times I ever did was during basic training, and later in 1979, when I was stationed further north, in Okahandja. More of that later though.

Early days in Windhoek

By early January I was settled in Windhoek and soon made friends with another National Service Lance Corporal, who was due to finish in July 1979. He was a most fortunate fellow as he had somehow managed to get himself accommodated in one of the few permanent barracks, each with a series of individual rooms, and he had one of the latter to himself. I never did find out how he managed this, as these barracks were supposedly for allocation to PFs only.

Anyway, my new friend bought himself a .32 inch semi-automatic hand gun not long after I arrived in Windhoek, and I went out to the local army range a couple of times with him to do some unofficial shooting. Basically, we propped up some cans on the fire wall and tried to shoot these off, and although my aim was a little better with the semi-automatic than it ever was with a rifle, I was still a bad shot!

This hand gun was almost the death of one of the PF Privates, and the cause of my own demise through sheer stupidity too. I was visiting my mate and sitting on his bed, playing with his hand gun. By playing, I mean loading the full magazine, cocking the gun to load it and then removing the magazine. After that I re-cocked the gun to eject the bullet in the chamber and then, taking the safety catch off, I would discharge it harmlessly, as it wasn't loaded anymore. What inevitably happened was that we were all chatting animatedly while I was doing all this, and I finally missed the all important step of ejecting the bullet that I had loaded into the chamber.

This PF Private had come up to the room's window from outside, and was leaning in the open window talking to us. As I had done a few times before, I raised the gun and pointed it out of the sealed window pane right next to him, no more than a foot from his head, and pulled the trigger, intending to discharge the cocked weapon harmlessly.

BANG! - I think we all jumped about six feet, and I thought I was going to have a heart attack. You can imagine the fear in me at that moment; not only had I discharged a live weapon in the confines of an army camp, but I had come within a foot of killing someone with it! There was this neat hole in the window I had aimed at, an obviously bullet shaped hole too, and the PF Private was as white as a sheet. Luckily for me, my father had taught both my brother and I how to handle a firearm as youngsters, and one of his golden rules was never to point the gun at anyone, whether loaded or not. I had always followed this advice, but was never more grateful to my father than that day, when his advice saved me from shooting someone dead through my own stupidity!

I very quickly handed my friend his smoking gun, and in fact never laid a hand on it again after this incident. It had scared me badly to make such a stupid mistake, which was perhaps the best outcome. We still needed to cover up, so we hastily checked to see if anyone was responding to the shot, but as it was a Sunday morning, there were few people around at the base camp and, more importantly, almost no PFs. The bullet I fired would have travelled over the kitchen roof and landed somewhere beyond. Again, I was lucky as the only thing beyond the kitchen was open ground, the main gate, a road in front of the camp and bush beyond this. I suspect the bullet landed in the bush, and nobody, apart from us, heard or saw a thing.

There was still the bullet hole to sort out, but we got round this by breaking it up a little more and then reporting that we had accidentally thrown a ball through the window while playing outside. Our explanation was accepted at face value on Monday, and a more relieved roof you would not have met.

On another occasion, a couple of us were sitting one evening outside and enjoying a late cup of coffee. Without thinking, I put my cup down on the ground for a minute, so that I could demonstrate the point I was making just then. Having finished, I picked up my cup and had a swig. The coffee seemed to have quite a bitter taste to it all of a sudden, so I walked over to a light to look closer, and discovered that my coffee was full of ants! They had found my cup on the ground and no doubt liked the sweet taste, as I have always had sugar in my hot drinks. I'd swallowed not only coffee, but a mouthful of ants too!

With their usual lack of organisation, the army also lost track of me briefly at the beginning of January. After receiving a few letters from my parents and Sharon, I was summoned one day in mid January by Sergeant Vermaak at SWA Command HQ, but no explanation was given me. As all soldiers do, I wondered what I'd done wrong, but it turned out that he wanted to know why my mother's letters to me were being returned unopened to her, and marked `unknown'! I assured him that I wasn't sending her letters back, and he said he would investigate further. To his credit, the letters duly started coming again, although I still don't know why only my mother's letters were returned. All of those written by Sharon reached me safely.

Private Tony Pereira, Corporal Venter and Private Joe Ferreira in the kitchen at base camp, Windhoek.

Hotlink to the Next Chapter.

Published at Sentinel: 24th July 2006.

Here is a shortcut back to

Sentinel Projects Home Page.