Chapter Five

Okahandja, Further North at Last

Okahandja - a pioneering move

By the middle of February 1979 I was heartily sick of working in the base camp kitchen, as we were still very much under the thumb of the many NCOs there, and constantly being harassed for one reason or another. I felt as if my whole world had turned to shit and I was furiously trying any gypo (dodgy scheme) to get leave so that I could go home to Johannesburg.

Included among my schemes was an application for leave to write banking exams, which I handed in to Staff Lourens. He promised me he would forward them, but I found them in his drawer, unsigned and unsent, at the end of January. The bastard had just quietly shelved them! No amount of pleading on my part would shift him though, and my application for leave was never considered, never mind approved.

Then, around about the 20th February, myself and Johan van Wyk, another Private, were summoned by Staff de Souza, and informed that we were being transferred north to Okahandja, where a new army camp was being started up just outside the town. He stressed upon us the importance of our assignment as we were to go alone, with no NCO chefs or assistance from SWA Command initially, and we would be in charge of the kitchens at Okahandja. It turned out that his description of our working place as a `kitchen' was a generous use of the word!

However, this was great news to me, especially given my frame of mind at the time. Here, at last, I was off to the war and getting away from all the base personnel in Windhoek, with all their stiff and starched attitudes.

Okahandja in 1979 was a sleepy town located 75 kilometres north of Windhoek, its main function being to service the local farms and railway. The word Okahandja means `the place where two rivers flow into each other to form one wide one', the rivers in question being the Okakango and the Okamita. As is the case in many of the hotter parts of Africa, these rivers were seasonal and only flowed in summer when the rainy season was in full swing, while being dry in winter when it was generally colder but much drier.

Late February was still in the middle of the summer rainy season, especially further north where there had been a number of attacks on SADF bases made my Swapo insurgents in February, and a number of clashes between SADF soldiers and insurgents, which had led to the deaths of men on both sides, although Swapo losses tended to outnumber ours by ten to one or more. Swapo were always more active in the rainy season as it allowed them to move more freely across the border of Angola, into South West Africa, and the rain would frequently wash away their tracks, making tracking them difficult.

The road between Windhoek and Okahandja. You didn't have to be out of Windhoek for long before you were well and truly in the bush, with only the road to indicate any sign of civilisation. Unfortunately, I never took a single photograph at Okahandja, so have had to `borrow' a few from other sources.

Besides our transfer to the town, we were not given much information, but were bundled into a truck, with a few supplies, and had a mobile field kitchen attached behind the truck. A driver was tasked to drive us to Okahandja. I wasn't sure what we would find there, but it proved to be pioneering army service in many ways. We arrived at the `camp', only to discover that it was out in the bush south of the town, and some distance from civilization. The camp was no such thing, merely a collection of old derelict buildings surrounded by a wire fence. I suspect it had once been a school judging by how the buildings were laid out.

As you drove into the main gate, there was a row of what could only have been classrooms, behind which was a large open area, similar to any playground found in modern schools. Off to one side there were more classrooms, and a communal shower and toilet block. As fancy as this sounds, it was all of these things in name only, as the buildings were all shells, with no windows or doors, these having long since disappeared. Now there were just the open holes where they would have been once, and everything was filthy and very dilapidated. The taps, toilets and showers didn't work either, and there was as yet no running water.

South West Africa Military School, Okahandja - February to May 1979

On arrival we reported to the Commanding Officer, a Major, who informed us that we had to set up our own kitchen as best we could, using the building at the end of the front row, nearest the main gate. This proved to be completely empty apart from a few work benches, which is why we had been sent with a mobile field kitchen, as the latter would be our only means of preparing food. It wouldn't fit in the building either, so we had it parked out the back, on the open field side, and prepared as best we could to cook for the few men currently stationed at the new camp. These numbered about 20 men, including ourselves, and for the most part we still had no idea why we were even there.

Many years after I had left the army, I discovered that this new camp was eventually known as the South West Africa Military School, and it was officially established in late 1979. However, when we started it all at in February, it was simply known as SWA Command Training Wing, and it was destined to be the main training facility for NCO's and other ranks of the South West African Territory Force, or SWATF, then in the process of forming.

Upon our arrival we still had a lot of work to do to clean up the building that had been allocated as our kitchen, set up the mobile kitchen, and hope fervently that the rest of our supplies and equipment arrived from Windhoek before the first intake of men did. We were fortunate as we received some eggs, milk, butter and meat just before the first group, nine black Corporals who were supposed to be doing their Platoon Sergeant's course, arrived on Monday 19 February, so we could at least feed them.

In the meantime, Johan and I were also allocated sleeping quarters, which were in one of the rooms in the same block as the showers. I think, in hindsight, that this room was also not a classroom, as it had a drain all the way around three of the walls, although there was no evidence of any taps or water pipes in the room itself. It had a large open window, or a hole where one had been, plus the open doorway (also without door), and we managed to scrounge two iron beds and mattresses from the supplies being delivered by truck almost around the clock.

We soon found a major flaw with our sleeping accommodation, mosquitoes! The river ran past the camp, just the other side of the perimeter fence closest to our room, and we could actually see the tall water reeds about 10 feet away from our window. As I've already mentioned, it was rainy season and the river was flowing. Our first night in Okahandja turned out to be a sleepless nightmare! There was no hint of the mosquitoes during the day, and we went to bed after a fairly hard working day, looking forward to a good sleep. We had hardly turned in when the familiar whine of mosquitoes started, and for the rest of the night, despite our best efforts, both of us were chewed alive. We couldn't close windows or doors and the mosquitoes just came and went as they wished.

I was so tired and disgruntled that I wrote home complaining about them, and have forever been teased since about my description of the night. I was a little over the top, suggesting in my letter that our walls were covered in blood from the various engorged mosquitoes we had killed, but we killed many and we had to wash our walls the next day.

Neither of us could face another night like that, so the next day we walked in to Okahandja, where we found a pharmacy, and we bought just about their entire supply of mosquito coils. The next night we laid these all around our beds and lit them, and enjoyed a good night's sleep. We spent a lot of money on these coils while I was stationed in Okahandja, but every cent was worth it as the mosquitoes were never quite as troublesome to us again, even though their numbers never diminished.

Daytime temperatures were very hot, and we worked with rolled up sleeves and spent as much time outdoors as possible. We weren't to be alone for long though, as our CO advised us at the end of February that a Lance Corporal from the local Commando unit would be called up to help us (and to take command of the kitchen, no doubt). He seemed concerned that we might resent this, as the Lance Corporal was a woman, but I personally didn't care. It meant that she would get it in the neck if there were any problems in the kitchen or with the meals! Much to our surprise the Lance Corporal turned out to be a middle aged grandmother, Lance Corporal Packett, and although old and wrinkled looking to us, she proved to be one of those salt-of-the earth people who make a lasting impression on you, and whom you never forget. Soon after her appointment she was given a two step promotion to Sergeant, to go with her new position.

By the beginning of March, numbers at Okahandja had swelled to 70 men, which included permanent camp soldiers like ourselves, and recruits. The latter now comprised 38 new trainees from 31 Battalion plus some men from the local Commando. The 31 Battalion soldiers were all Bushmen, and excellent trackers whose exploits in tracking Swapo insurgents was legendary, even then. Many of the 39 were NCOs at least, and the place literally crawled with Corporals and Sergeants, although they ignored us and we did the same to them. I found them to be fascinating people, with a very strong sense of duty and community. Even after hours, when they showered in the communal showers, they would do so together and in a large group, often grooming one another. One form this took was to generously lather basic laundry soap, then coat their tight curly hair with it, and have a friend comb it into neat lines for them. It made my scalp itch just to watch them!

My time at Okahandja also introduced me for the first time to non-racially based living, as we only had one set of showers, one set of toilets and one mess, and everyone used them. It felt so natural that I was amazed that I had ever considered separate toilets etc., such as we had in South Africa, to be normal. To be honest, I found the various black soldiers to be generally more tidy about their appearance and their habits than some of the spoiled white ones were!

I didn't have much to do with the men attending courses at the camp, as they were kept busy by the resident instructors, but one evening, after hours, I had a fairly long conversation with an Ovambo Sergeant from 33 Battalion, who was there on a course. He told me he was a married man with children, and had joined the army voluntarily, which I assumed was because he needed the employment. Much to my surprise, he said this wasn't the case. Instead, he expressed quite a strong viewpoint of the so-called Swapo `freedom fighters', who he said threatened and kidnapped many Ovambos, and were more of a menace than the security forces. This was why he had joined the latter, not because he supported apartheid or wanted to be in the army, but he wanted to protect his family and found the security forces to be the lesser of two evils! I came away from this conversation with a newfound respect and admiration for the Ovambo, who were the meat in the sandwich always between us and Swapo. They were a peaceful and dignified people mostly, and deserved better treatment from both sides than they actually received.

This is not to say that Swapo insurgents were innocent angels - they certainly were not - and they too were Ovambo. They could be very cruel and callous, but also very brave, the latter characteristic one you just had to admire. I was to find out first hand how determined they were too.

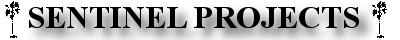

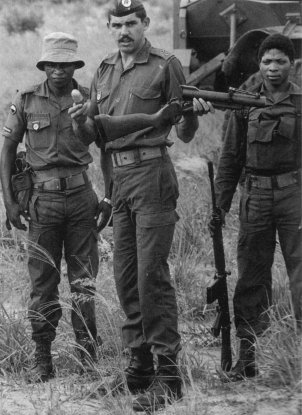

Bushmen soldiers under instruction by their white officer (on the left) and Ovambo soldiers at their base in Ondangwa.

Early days in Okahandja were pretty good, as I had finally achieved what I had wanted since being told I was going to South West Africa, an operational posting of sorts. Although below what was considered the main operational area, Swapo insurgents were known to penetrate in small groups as far south as Windhoek, their aim being to disrupt and sabotage wherever they could. This usually took the form of laying landmines in the roads, an effective and relatively safe way of striking at us, as the mine layer was usually long gone by the time some unfortunate rode over the mine. While in South West Africa I saw my fair share of military and civilian vehicles that had been unfortunate enough to trigger one, especially at the tiffie workshops in Windhoek, and while the army Buffels and other vehicles stood up pretty well to the blast, civilian vehicles tended to be blown to bits, along with their unfortunate occupants. Our army vehicles at the time had their tyres filled with water, rather than air, and although this shortened the life of the tyre, the water acted as a great shock absorber when the tyre exploded a mine. Often, the only result was that the wheel was blown off, everyone received a nasty shaking, and the vehicle came to a grinding halt in the crater.

Our camp Sergeant Major, Schultz, was something of a disciplinarian but was always good to us chefs. I think he felt sorry for us as, unlike the rest of the staff at Okahandja, we were not instructors and were more support staff. As an example of how tough he could sometimes be, one afternoon he called at the kitchen to asked if we had set a menu for dinner that night. I replied that we had not yet done so, and he ordered me to make only soup, nothing else. All of the trainees were out in the bush doing some strenuous route march that day, and he knew they would be starving when they arrived back at the base. While they were out he had done a snap inspection of their tents and quarters, and was not pleased with what he found, hence the soup. They were a very pissed off group on their return to camp, when they were confronted by my thin, watery soup and a piece of bread each for dinner!

The only others like us chefs at Okahandja that I can recall were a couple of PSC clerks and our resident Medic. The latter, a Private, was a very self-confident type who positively oozed charm, especially around the local girls.

The girls, and there were only a few truly pretty ones, were very happy to see all these young men around their sleepy town, and not a few went out with soldiers while I was there. I was presented with a rather strange request one afternoon by a young infantry 2nd Lieutenant at our camp, who asked me if I wanted to go out on a date with him and another 2nd Lieutenant that night. To say I was taken aback is putting it mildly, as these two officers were not even close acquaintances of mine, let alone friends. Also, I was quite happily engaged to Sharon back in South Africa, and said so. This brought forth the true reason for my `invitation'; the two girls that he and his fellow officer wanted to date, had a younger sister who might `get in the way', should their evening go well! As I had nothing else to do, I agreed, but only on condition that all I was required to do was keep little sister out of their way. We duly arrived in town in our civvies, and the first few minutes of conversation were very awkward as the two Lieutenants tried to pretend they knew me and vice versa. Their evening did `go well', and once they and the two older girls had retired to more discreet settings, I spent the rest of the evening playing cards with the younger girl, who was only about 13 years old, if she was a day.

In mid March we were shocked out of our small town complacency one Friday afternoon. We never in our wildest dreams believed that Swapo would dare show their faces so far south during their annual infiltration of South West Africa, but a few brave (or foolhardy!) insurgents did just that.

It was a typical Friday too, with all of the PFs, plus any ranking National Servicemen, setting off south for Windhoek, and a bit of civilisation for the weekend in the late afternoon. By the time everyone had gone, there was just us two National Service chefs, and one or two other Privates, clerks if I recall, left at the camp. I was standing outside in the front of the main buildings, when I saw an infantry armoured column of about ten vehicles, including Buffels and at least one Ratel, approaching the camp along the main road, from the direction of Okahandja itself. In other words, they were heading south, towards Windhoek. Much to my surprise, the Ratel pulled over at our main gate as if to enter, and the officer in the turret (a Commandant, if I recall correctly), called me over to the vehicle. He asked me who was in command of the camp, so I told him the Major was, but told him the latter had already gone home for the weekend. He then wanted to know who was in command at the moment, and I had to confess that nobody was, as there were just us few Privates left for the weekend.

Without a blink, the Commandant informed me that his column was actively tracking a small cell of Swapo insurgents, now in our immediate area, and as the ranking officer now present, he was commandeering our camp as a base for his men, to enable them to patrol and sweep the area on foot. We had heard nothing of this before now, and I am sure that had our PFs known, they would not have been so quick to take off to their homes that Friday.

The vehicles drove into the camp and the infantry, about a platoon, clambered down and moved into our guard tent at the main gate under orders from the Commandant. He then asked if Johan and I had rifles and ammunition, which we did (our G3's and two magazines, or forty rounds of ammunition each), and he informed us that we would have to stand guard at the main gate to check all vehicles in and out, as he needed armed men there and couldn't spare the infantrymen in his task force for this. So, in five quick minutes, I had stopped being a chef and become an infantryman and sentry once more, right in the middle of a war, or so it seemed. Nowadays I think we never were in any real danger at the camp, as a few armed Swapo guerrillas were not suicidal enough to attack a camp full of infantry, all armed to the teeth, but I wasn't so sure of this at the time!

Johan and I moved into the tent with the infantry guys, and spent the rest of that weekend with them, on and off. They were all National Servicemen, mostly riflemen with a 2nd Lieutenant in command, and a Corporal and two Lance Corporals under him. A more grizzled lot you never did see, and they looked as if they would kill their own mothers if ordered to. It was my first encounter with men who had that distant stare, and who had probably seen and done things that I was never likely to do. I envied them then, but now I don't and am pleased I never had to do anything that would be on my conscience for the rest of my life.

That weekend was one of the most exciting for me, as I was in the middle of the shooting war at last, and not just some base slave. My excitement was not matched by the infantry guys, and I understand why too. They had to do the patrolling and if need be, fighting and dying!

A restless night followed in which much activity went on around the camp to set up a base of operations, during which Johan and I made coffee for everyone or stood guard and watched all this unfolding. The Saturday morning started early with the infantry cooking up their own breakfast from rat packs and cleaning their rifles or machine guns, while taking little trouble with any personal grooming, such as combing hair or washing. I noticed that they were all on first name terms too, and there was none of this "yes Sir" mentality that prevailed normally in Windhoek. The Lieutenant was definitely in charge though, and although he tolerated his men addressing him by name, I also noticed that they followed his orders without hesitation or question. Another oddity I noticed was that he wore no rank insignia, and neither did his NCO's. None of them were distinguishable from the riflemen, which I was told was the point when I asked. If ambushed themselves, the terrorists would not be able to easily identify who was in command and kill him first, rendering the remainder of the patrol leaderless at the start of a fire fight.

Saturday was a constant hive of activity at Okahandja, with infantry patrols moving off at first light to search the surrounding bush, and more vehicles arriving with additional men, to join in the pursuit. As each patrol came in again with nothing to report, you could sense the real frustration, and the Commandant and his officers would send the patrols out again after a brief rest, to search in a different direction. I was so happy to be able to help in my own small way that I didn't even notice the lack of sleep, neither Johan nor myself being able to sleep while on guard duty. As a result we had been up since Friday morning.

By nightfall nothing had been found, and the infantry returned some hours after dark for the last time, to settle down to a few hours more sleep in our guard tent, while we stood guard and imagined all sorts of gunfire being directed at us from the surrounding bush. It sounds laughable to say this now, but I was that green then that I knew nothing of the infantryman's war, or even the tenacity that could be displayed by Swapo insurgents. They did attack army camps, but were generally not suicidal and would do so infrequently and only at dawn or dusk usually, to minimise their own casualties and reduce the risk of successful follow up by the security forces. I was never to be in a camp that was attacked during my entire service in South West Africa.

Saturday night passed uneventfully, except that by now both Johan and I were living on coffee alone, as we had been sleepless for almost 48 hours. On Sunday morning the tired infantry set out on patrols once again, with equal lack of success, at least through the morning. While they were out I obtained permission from the Commandant to walk into town as I needed to buy some personal supplies for us (cigarettes among them!). He agreed but made me take my rifle with me. I wouldn't have gone without it anyway!

It was quite a walk into the town in those days and this was separated by sections of bush along the road. I walked the whole way, expecting to be ambushed at any moment from the surrounding bush - a very creepy feeling! Of course, I wasn't, but it was a great relief to get back into camp again, and the safety this offered in numbers.

South African infantry patrolling in dense grass along a river line. This scene was a daily occurrence for the infantry on foot patrols. They were the real heroes!

In the late afternoon there was great excitement in the camp as news reached us of a brief contact with the insurgents. Evidently, one infantry patrol had been sweeping in line and a rifleman surprised a group of three armed men. An exchange of fire left one insurgent dead and his colleagues scattered in all directions. There were no casualties to our soldiers. At the time I was elated, and swept along in the euphoria of it all, but in hindsight I am sad that anyone had to die.

With the immediate threat to the area now over, the operation at our camp wound down, and guard duty that Sunday night was very tedious and tiring. By first light on Monday the armed column were again packed and ready to move on, and we watched their departure before preparing breakfast for the trainees, many of whom were by now putting in an appearance from their weekends at home.

We were still preparing breakfast when Sergeant Packett arrived for the day and we informed her of the weekend's adventures. When told that we had stood guard at the main gate all weekend without relief or sleep, she ordered us both to our beds there and then, and took over the preparation of breakfast.

The bed never felt as good as it did that morning, and I have little recall of even putting my head down on the pillow, I was asleep so fast. I woke later to bright sunshine outside, and when I checked my watch, the time was about 11 am. I thought I'd only slept for a few hours but, feeling a lot better, I got up and dressed and went outside. There I met Johan, who laughed at me and then told me that it was in fact 11 am on Tuesday morning, and I had slept solidly for about 27 hours! To this day, it's the longest I have ever slept, and shows just how exhausted both Johan and I were. He had, in fact, only woken up about an hour before I had, and been equally astonished to discover how long he'd slept. Sergeant Packett had taken on all the cooking duties herself and left us undisturbed, for which I was very grateful.

Routine at Okahandja

With the Swapo insurgents now dealt with or scattered, our routine returned to one of daily cooking with the odd break for recreation. As neither Johan nor I had personal transport, we tended not to go south to Windhoek, but stayed around Okahandja when we were not working. The town itself had a certain charm in 1979 as it was still very much an example of German colonialism at its finest; old but well built buildings which were gaily painted and shone nicely in the prevailing sunshine.

I still looked forward eagerly to my many letters from Sharon, and she and my parents took to sending me the odd song request on a radio program called Forces Favourites, which was broadcast on one of the South African Broadcasting Corporation channels each Saturday and Sunday afternoon. It used to bring a lump to my throat to hear my name read out by the hostess, Pat Carr, together with the `love you and missing you' message from them, but I always appreciated it too, as did all the guys lucky enough to get a greeting from home. We really did miss home a lot.

Television was still very much in its infancy in South Africa in 1979, and there was no television in South West Africa at all. Okahandja also had no theatre or cinema, so our only source of outside news and entertainment was a portable radio and my cassette player. We used to listen to rugby commentaries on the former, and I still recall listening to a game played in Windhoek between the Orange Free State and South West Africa, won by the former but not before they had been given a fright by their less fancied opponents.

Okahandja Station, still the original German building (1903, inset right).

Home at Last, and unexpectedly too!

The Thursday before Easter, 12 April, started like most other days in Okahandja, but before the morning was up I had set off on another long journey, which in hindsight was a bit hair brained on my part! It is proof though of just how much I missed Sharon and home.

With a long weekend of four days very much in prospect, our PF's decided that they would let all the trainees go home early on the Thursday, at about 9.30am, to enable them to get to their homes further north. This was also a clever ploy to get the weekend off themselves, and by 10am all of the PFs, trainee NCOs and officer instructors had disappeared, either home or to the relative civilisation offered by Windhoek. Johan and I were forgotten in all this rush, and were resigned to spending the weekend around the camp, as we had been given no leave.

Then, much to my surprise, Sergeant Packett told us both to bugger off as she had no intention of staying around the camp when she had a perfectly good home to go to in town, and besides there was nobody to feed either! A few men were staying in camp, either because they had sentry duty to perform or because it was too expensive or inconvenient to go anywhere, but she said she would come in each day and make meals for these few herself, and with no senior officers to stop her, she signed both of us out on weekend leave from that Thursday morning until 6 am on Tuesday the 17th - almost four whole days! Bless you Sergeant Packett!

That was enough for me, and my youthful optimism kicked in big time! I grabbed my rifle and ammunition, plus a small bag with a few clothes, and without a second thought headed out of town on foot, hitchhiking towards Windhoek. I wasn't going there either - it was home I was headed! When I think about it now, I'm convinced I was mad, but the whole idea made perfect sense at the time. I never gave a thought as to how I would reach home safely, or how I would get back to Okahandja. All I thought about was going home! Being in my uniform, I had no problem in getting a lift with a truck driver heading for Windhoek, and he obligingly dropped me off just outside the city on the main road leading south, where all the soldiers hitch hiking to South Africa stood.

The soldiers standing there that day were mostly dressed in full dress uniforms and were going home on long leave, having added their seven or fourteen days of annual leave to the Easter break, to make their stay at home longer, but I didn't care. My supreme confidence told me I would make it home (some might call it arrogance!), and sure enough, I had barely stood for two minutes with my rifle slung over my shoulder, when a car driven by a young guy with an even younger girl stopped and picked me up.

Sadly, I cannot remember their names now as we only spent two days together, but he was a young Afrikaans farmer from the Tsumeb district, and the lass was his younger sister. They were on a pilgrimage of sorts, as he was driving to South Africa to meet up with and marry the girl he had fallen in love with while in the army himself, and stationed in Pretoria!

How lucky can one troep be!? Here was someone travelling to Pretoria, further than I wanted to go, and he had stopped to pick me up! Evidently, the plan was for him to get married in Pretoria, and then his sister, he and his new bride would drive back to his farm in Tsumeb, to live. He was a little disappointed to discover that I didn't know how to drive, as I'm sure he was hoping I would reciprocate his kindness by giving him a break and doing some of the driving. His sister also couldn't drive and it was a long way to Pretoria! He never hesitated though, and I was soon happily speeding south again with him and his sister.

He told me that we would be making an overnight stop at Rehoboth, to visit their older sister and her family, which gave me my one and only opportunity to see this part of South West Africa. Rehoboth was a dusty little town, mainly there to service the local farms and railways, and this young farmer's brother-in-law worked for the railways. I felt a bit awkward, turning up unannounced at these people's house, but they were kindness itself and made light of my unexpected arrival. I was made to feel welcome and given a bedroom of my own to sleep in.

We had arrived in the late afternoon, and preparations were made for a braai (barbeque) while it was still light. Then we cooked up a feast, and they plied me with beer and friendly conversation until quite late.

I was woken at about 3am on the Friday morning and quickly dressed and made ready to continue our journey. We had a long drive ahead of us before we hit the next main town in the south of the country, Keetmanshoop, and the farmer hoped to complete this before the heat of the day. He also wanted to make Pretoria that same day, and even leaving as early as we were, he was unlikely to see Pretoria before nightfall. In my haste to get ready, I left my beret and one of my rifle magazines with 20 rounds of ammunition behind at Rehoboth, a fact I only discovered many hours later when we stopped in Keetmanshoop to buy a cold drink. At the time I just shrugged their loss off, but both items were to haunt me later!

The hot day passed slowly, as we drove for mile after mile along the straight road, surrounded by alternating patches of flat dessert or tussock, but we kept up a lively conversation and I for one got more excited as we approached South Africa. After a brief stop in Keetmanshoop, we eventually crossed the border and drove steadily through the Northern Cape and then North Western Transvaal, the young girl sleeping while I chatted to her brother and at least helped to keep him awake and focused on his driving.

As we approached my destination, I expected to be dropped off outside of Johannesburg, as this was the easiest thing for the farmer to do. That way he could continue past Johannesburg straight to Pretoria, but he would not hear of it. Instead, he insisted on dropping me off as close to home as possible, another example if his great kindness. With his limited knowledge of Johannesburg and the southern suburbs to consider, plus the late hour (dusk was now upon us), he drove right into the southern suburbs but decided to drop me off at a major intersection on Rifle Range Road. From here I could walk home in about 45 minutes, and he could easily rejoin the M1 motorway, which went north to Pretoria.

He duly dropped me off in the gathering gloom, and we wished each other well before he and his sister drove off and left me standing there. I never saw them again, but have always remembered them and hope that he and his wife are still happy and healthy together. He was a nice guy, and certainly deserved all the happiness he obviously felt then. I thought so anyway, but I was biased - he'd just given me a lift from Windhoek to Johannesburg, and entertained me royally along the way!

I was still standing on the side of the road, waiting for an opportunity to cross over and begin the walk home, when a civilian car pulled up next to me and the driver called me over. I thought it was someone wanting to offer me a lift, and was just about to decline the offer when the jumped up bastard started giving me a hard time! Before I could collect my wits, he wanted to know who I was, why I was out in combat uniform instead of dress uniform, why I was armed, and where was my beret? To say I was pissed off is putting it mildly, but the stupid little turd, although wearing civvies, produced an army ID, showing that he was an officer, so I had to bite my lip and answer as best I could. I explained I was home on leave and was just about to walk home, having been dropped off, but this didn't satisfy him. He threatened to report me for being improperly dressed (no beret) and for having my loaded rifle with me, and asked me for my unit. By now I was really pissed off, so gave him a sullen stare and said "South West Africa Command, Sir!" That finished the conversation, as he knew he could never find me there and even if he did, nobody would care if I had been in Johannesburg without beret, or that I had been wearing browns and not dress uniform. With an angry comment he dismissed me and drove off again, while I walked off without a second glance, hoping he'd have a nasty accident somewhere down the road. I never heard another thing about this particular incident, so if he did report me, it came to nothing.

It was dark by the time I reached home that Friday evening, but as tired as I felt, the reunion was the best of my entire two year service. Nobody was expecting me home, and as Sharon lived with my parents now, everyone was there. My poor mother fluctuated between excitement and stress as I presented myself, grubby and armed with a rifle, on her doorstep. She hugged me, asking at the same time how and why I had come home. When she discovered that I had hitch hiked home from Okahandja, a distance of over 2,000 kilometres. She was horrified, especially when I told her that I intended hitch hiking back too. She would not hear of it, and went out with me the following day to buy a return airfare to Windhoek for me. This meant that I had three whole days at home before I was due to fly back on the Monday night, and three wonderful days they were too!

As with all leave though, it was over too soon and after an uneventful flight back to Windhoek on Monday afternoon, I managed to catch a lift back to Okahandja that same evening.

At Okahandja I was greeted by Johan with the news that I was to be promoted to Lance Corporal. I did a few discreet enquiries on the Tuesday, which seemed to confirm this news, so I approached Sergeant Major Schultz directly about it. He told me that I had been recommended for the promotion, but I was to keep this to myself as it had not yet been confirmed. Sadly, in the end it proved not to be, as I was transferred away from Okahandja before the promotion came through and, with the Lance Corporal being required at the latter, someone else was selected for the promotion. This was very frustrating to me at the time, not due to any narcissism on my account, but because I was hoping to get the extra pay! It was also not the only time I was to be passed over for promotion due to circumstances beyond my control.

My return to Okahandja was also soon followed by more Swapo insurgent activity in the area. A fairly large group had infiltrated the Angolan / South West African border some weeks before, and a few of these were reported to have infiltrated as far south as Okahandja.

On Wednesday 18 April, two days after my return from leave, Sergeant Major Schultz ordered all base personnel to draw weapons and ammunition from stores if they did not have any (most of the instructors didn't). Johan and I already had rifles and ammunition, and said so, but I didn't let on that I had lost half my ammunition! The infantry trainees were also told to prepare for a patrol at short notice.

To be honest, I thought it all a bit much to believe and was quite casual about the prospect of meeting up with some desperate Swapo intent on doing me harm. It was therefore much to my surprise, and some embarrassment, that the infantry trainees and instructors, mostly experienced NCOs and officers, were hastily assembled at 2am the following morning (Thursday), and sent out on patrol to search the surrounding bush, while the rest of us had to stand to. The infantry stayed out for two hours, but found no sign of the alleged insurgents, and we were stood down later that day, after receiving reports that the insurgents had moved out of our area and on towards Windhoek. Whether they were ever there on this occasion I still don't know, but Sergeant Major Schultz certainly believed they were. He even stayed in camp that night, rather than go home to Windhoek.

People may scoff at the idea that Swapo insurgents infiltrated so far south from the main operational area in Ovamboland, but I have since read of a few whose exploits became almost legendary. One small group of insurgents evidently penetrated as far south as Mariental in 1981 and after being turned back, were pursued north again for two weeks. They covered as much as 600 kilometres on foot and eventually escaping back over the border into Angola. Mariental is 261 kilometres south of Windhoek and some 335 kilometres south of Okahandja.

Hotlink to the Next Chapter.

Published at Sentinel: 24th July 2006. Here is a shortcut back to