Becoming Apartheid's Soldier

Infantry School, Oudtshoorn (1975)

David attended School of Infantry, Oudtshoorne (1975) and was then a training Lieutenant at 7 SAI (Bourke's Luck) and 4 SAI (Middelburg) for 1976. With a liberal background he has issues with the political system which interacted interestingly with his desire to be the best soldier that he could be.

When one turned 16, the school registered you for conscription. A few months later you received a confirmation that the SA Defence Force had your details. One never imagined at the time how sinister this was. It plagued us for years.

White schools, of course, in the 1970s were policed by the Christian National Education (CNE) policy, which enforced a conservative Christian outlook, and the narrow nationalism of the ruling white Afrikaner power-mongers.

This Crusader-like attitude devolved in the form of daily prayers and hymn-singing, the all-too-frequent singing of the national anthem – and cadets once a week. You wore a khaki uniform and beret. I got out the worst by joining the military band as a drummer boy. Carrying a side drum was much more stimulating than plain marching!

Drawn by the earlier military influences of my father, my shooting practice up in the hills, and a boy's natural attraction to guns, I joined the school shooting team, and became a crack shot with a .22 rifle. This was fun. We had a rather roguish counter-cultural teacher supervising us, who used to wear a red scarf tied around his neck, and who looked a bit like Trotsky. Having just seen Attenborough's film 'Doctor Zhivago', I could imagine us being part of the Red Army and achieving heroic exploits.

So while the other boys played sports or did cadets, we went up to the top corner of the school, to a little 25-yard shooting range, where we practiced. I soon made the Bisley Team, and we travelled to East London, and notably, to Port Elizabeth, where we visited the army shooting range, and stayed in army huts near the Humewood beachfront for a few days.

For the nerd I was at school, stuttering and bullied by others, my self-esteem was very low, although inside I knew my own worth. This is what carried me through five years of hell.

By the end of school in 1974, I had received my call-up papers to the Anti-Aircraft School at Youngsfield, in Cape Town.

Politically, things were quiet. John Vorster ran the country with heavy eyebrows and an even heavier hand. My military ID number was 72414824, a number that would follow me for years. I still remember it now.

The Watergate scandal broke in the USA and India tested their 'Smiling Buddha' nuclear weapon. Isabel Peron rose to power in Argentina. Turkey invaded Cyprus and Richard Nixon resigned, replaced by Gerald Ford. Haile Selassie was ousted in a coup by the Derg. The IRA bombed the Tower of London, further proof of 'terrorism' for our fascist government.

Of great interest was the 'Rumble in the Jungle', between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali, held on 30 October in Kinshasha, Zaire. Ali was fighting to regain his title. Zaire was a place of darkness and mystery, in deep tropical Africa, romantic and idealised. I was glad Ali won his heavyweight title back, but I always have been revolted by boxing. I thought it a barbaric blood sport I had experienced first hand with bare knuckles as a schoolboy.

West Germany won the 1974 Soccer World Cup at home. Alexander Solzhenitsyn was expelled from Russia. The almost complete hominoid skeleton Lucy was unearthed in Africa, and dated older than three million. Universal Product Bar Codes began on products in the USA. Computer watches and calculators appeared.

Films I saw included The Sting, Papillon, Blazing Saddles, and The Great Gatsby. Music I was listening to was Alice Cooper, Deep Purple, Genesis, Joni Mitchell, Queen, Roxy Music, Supertramp, Jethro Tull, and David Bowie.

Also in 1974, the Soviet Union launched the Salyut-4 space station, and the global recession deepened. Henry Kissinger brokered a ceasefire on the Golan Heights and Charles de Gaulle airport opened in Paris. I clearly remember Cyclone Tracy almost destroying Darwin, in Australia. There was also a coup in Portugal, led by General Antonio de Spinola. This had implications for Angola and Mozambique, which would both become independent the following year, although we did not know it at the time.

So after a happy Christmas 1974 and New Year with family, I was destined to head off to army for two years on 7 January 1975. On New Year's Eve I went to a party with a friend from down the road, on his 50cc motorbike. At the party, my drink got spiked, I think with cigarette ash. I only got home the following morning, with the worst headache and hangover of my life. I'd spent most the night vomiting. I felt very sorry for myself.

I was actually still very hung over when I reported for duty on 7 January, at the railway station in Braamfontein, with my guitar and longish curly hair. The army chaps looked fearsome as they herded us onto the train, tanned, fit, strong. We were all brave with our families, joking and laughing, not knowing what was about to happen. We waved goodbye as the train finally pulled out of the station.

Then the shouting began.

'Beweeg! Beweeg! Beweeg' the corporal shouted. I didn't know what the word meant, but I knew what I had to do: run! And so, after 12 years of not-really learning Afrikaans at school, and being completely hopeless at it, I would become fluent in Afrikaans in just two months! Everything was in Afrikaans. I think it took two days to get to Youngsfield, with an interminable wait in Kimberley, being shunted around as engines changed tracks.

In a letter to my father the following day, I wrote: 'The train left Jburg (sic) at about 10am and it was very hot. The water on the train was all warm and there was little of it. We arrive here at about 3pm on Tuesday and embarked on a long march to the camp.

My case never seemed heavier than it did then. I've got big blisters on my hands now . . . temporarily we are in tents . . . we are in a hurry all day long to go and sit in long queues all day long. I have got quite badly sunburned.'

Arrival in Youngsfield was greeted with more shouting. I was placed in C Troop, 102 Battery, 10 Anti-Aircraft Regiment. We were herded into groups, and shunted off for a medical examination in our underpants, then to the stores to get our 'browns' and equipment and back to the bungalow, T19.

Then we were herded off to the barber, where we all got shorn. Short back and sides, a Number 1. The hair piled up on the floor. This was a devastating attack on our persons. We looked like plucked chickens, white, frightened and all the same. I wrote: 'I have had my regulation haircut and look like a half-skin (sic) red goose!!! My Afrikaans is improving fast. We met our PTIs last night (Physical Training Instructors). They struck us with great fear. We get up at 4am here . . .

Over the next week we learned how to drill, to polish boots until you see your reflection (this process is called 'boning'). You begin by showering in your boots, so that they get soft. Then you wear them dry, and they fit like a glove. You can imagine the scene: 10 boys naked in the showers wearing just their boots! Then you iron the toecaps of your boots smooth with a hot iron. Then you smear polish on thickly and burn it. Then you begin to polish. After much elbow grease and spit, the boot loses its original combat dullness and began to shine like a piece of glass in the sun. Highly boned boots earned you respect. They could also attract a bullet in combat. Army contradictions.

We were shown how to set up our 'kas' next to our steel bed, with all the clothing extremely neatly folded and squared (everything had to be squared, even our blankets on our beds). We had to chew our blankets on the edges of the bed to create a sharp corner, and polished our lino floors into mirrors.

We spent hours preparing for inspection, our 'varkpan' (literally pig-pan, a stainless steel metal tray with compartments for food) and eating utensils laid out with our rifle and webbing. We would sleep on our 'mirror floors', with the beautifully made-up bed ready for inspection the next morning.

All spare time was spent shining buckles, boots, floors, rifle bores and badges. Nylon stockings are particularly good for shining boots. We each had a 'trommel' under our beds for personal stuff (snacks, biltong, biscuits, coffee, civvy clothes, chocolate, magazines, books etc).

We nearly all smoked. In between drill sessions on the parade ground, we would sit and smoke and look at Table Mountain and talk about what we would do after 'Basics', the first 12 weeks of training, during which we were not allowed to see anyone or leave the base. Between drill periods, we had to attend lectures and do practical training.

We learned to strip our rifles and put them back together blindfolded, to load a magazine with 20 rounds in under 20 seconds. Went to the shooting range for the first time to fire on targets 100m to 600m away, and learned how to sight-in our rifles and adjust for long-range shooting.

Most feared though, were the PTIs, the Physical Training Instructors. These corporals would take us for PT and work us mercilessly. Any tiny fault and you would have to 'sak vir vyftig' ('drop for 50' push-ups). There was lots and lots of running, running and running. You ran everywhere. You even drilled sometimes in double time (running in step).

And everywhere you went, you went with your rifle. Anyone who referred to a rifle as a gun would have to stand up on a box in front of his squad, holding his rifle in one hand and his penis in the other, and recite: 'This is my rifle, this is my gun, this is for killing, this is for fun.' We soon got the message.

One afternoon our corporal decided we had all failed to 'saamwerk' (work together). So he began to 'jaag' (chase) us up and down one of the roads between the huts, round a fire hydrant and back again. This is called 'strafdril' or 'punishment drill'. We were wearing our webbing, boots, and steel helmets. Each time with our rifles held over our heads.

An R1 rifle weighs 4.31kg, and in order to run with it, you hold your arms extended straight to each end, holding the stock in one hand and the muzzle flash in the other, behind your head. It's difficult but better than trying to hold it up with your arms bent! At least you can sometimes rest it on your helmet, but this would usually only incur another chase up the road.

This went on for some hours, until we had missed dinner and we were crying with exhaustion under the sickly yellow sodium lamps. Anyone who failed to hold his rifle over his head on one of the runs would incur the further wrath of the 'korporaal', who would then send the entire platoon back around the hydrant because 'julle maatjies wil nie luister nie, ne?' (your buddies won't listen, hey?') It was brutal, but then turning boys into soldiers is brutal.

The next morning my inner forearms were bigger, but black and blue with bruises. It only took a couple of hours to get two completely new bulging muscles that any gym-goer would be proud of and which would have taken him several weeks, even months to achieve!

I had signed up for two years when conscription was only one year, because you were promised a bonus of R3000 for the extra year. I needed this money to pay my first year's tuition at university. My parents would pay another year, and the following years I would get student loans. After this PT lesson, I was beginning to regret my decision!

Nevertheless, Basics proceeded well, and I excelled beyond my own expectations. All the boys with us from school, who had played first team rugby, cricket, swimming, or been prefects and those the school looked up to as heroes, did not perform as well as I did. I could run, and I had a mental toughness, probably developed by my stutter, that stood me in good stead.

In a letter home on 6 February 1975 I wrote: 'For every letter we get, we have to 'sak' for 10. We walked to the shooting range with full pack, about 10 miles and four guys in C Troop passed out. It was very tough.

'For grouping I scored 23/25 at 200m and 25/25 at 200m. Then in the deliberate fire I scored 730/1000 which means seven bulls which count for five, three shots in the next ring counting for 3 points and that was all. We only fired 10 rounds in the deliberate. So now I am thoroughly acquainted with my rifle.' I had qualified for a sharpshooter badge (bronze).

'Then we learned a lovely way of moving over terrain in an inconspicuous way; it is called leopard crawl. We also learned how to roll, etc. Then we went to a high sand dune which was about 60 degrees angle. Everyone says it was 75-80 but I reckon it was 60%. Pure fine sea sand interspersed with 'boompies' or small trees. We rolled down, with rifles and webbing, and leopard crawled up. Really killing, as you get utterly exhausted. Sweat became sand, bruises became readily apparent as we flung ourselves with grim abandon down this dangerous steep dune. I have never seen a rifle so full of sea sand. I spent two hours cleaning the sand dunes out of it last night.'

I outran my 'superiors', leaving them for dust. This was marvellous for my self-esteem, and one of the reasons why I look back on my military training with some nostalgia, not because I supported apartheid, but because it taught me my own self-worth, and it enhanced my own capabilities as a person.

The army developed me, not always in the right way, because the aggression that comes with training to be a soldier is not welcome, but because it, in the words of the cliché, 'made me a man'. It toughened me up, widened my experience, and showed me what the human body is really capable of. I became more confident in myself, and began to like my own physical body for the first time.

Round about the end of Basics, we had some road shows visit. The paratroopers from 1 Parabat Battalion in Bloemfontein arrived, as well as men from the Infantry School in Oudtshoorn, Armour School in Bloem, and terrifying men from the Reconnaissance Unit, the dreaded and feared 'Reccies', who were much better than Britain's SAS or the US Marine Corps. These guys had that '1000-yard stare' of hardened killers, and they looked dangerous and very capable. For a boy soldier, it looked very enticing.

But joining the Reccies meant signing up for three years, so I thought hard about it, and then decided No Ways. But my corporal had recommended me for Infantry School, where I would learn to be an infantry platoon leader, which I was more keen on than being in the woosie Anti-Aircraft Regiment.

Was I crazy? Why did I give up the chance to go ice-skating every week, hang out on Cape Town's beaches and joll (party) in Cape Town for a year? What on earth possessed me to sign up for the Infantry School?

I will never know. Pride, perhaps, a desire to achieve, and to escape my nerdish school days? To fulfil my father's wishes? In a letter on 13 March I wrote: 'I feel just hopelessly sort of beaten down. When I see others who aren't worth it being sent on officers course only because they presented a good picture to the selection board, gee, I can see that some of them won't make good officers, I just get depressed.'

Nevertheless, I made it to selection to the Infantry School, which was a much more elite unit than officer training in Anti-Aircraft. So, days after basics finished, I had a weekend pass to see my parents, and then I was off to the Infantry School at Oudtshoorn, in the middle of the Karoo. A hot, horrible hell.

I exchanged my blue beret for a green one, and the 'flash' (badge) of a burning cannonball for the Springbok. I was now in an elite unit, and very proud of it. I was assigned to Bungalow 447, Platoon 1, Course 3, B Branch. Life became very, very tough. I was paid 94 cents a day, which enabled me to get out (after military deductions) around R21 a month, of which I could save about R10.

I wrote on 17 April: 'Today the student lesson was the ill-fated leopard crawl that civvy street has heard about. And other sundry delightful movements that are exciting to watch but painful to demonstrate. To the uninitiated young boy, we are exciting heroes, but to our fellow sufferers (sorry, soldiers!) we are just inadequate men. I messed up my knee taking cover from 'enemy fire' on some particularly stony and thorny ground. I weigh 135 lbs now, from 115.'

And on 20 April: 'My rifle broke on Thursday when we did an ‘attack' on the enemy, and I clubbed one to death with the butt. The butt plate leapt off and a long oily spring did a dance on the dusty sand. The 'enemy', needless to say, had a large dent (it was a tin container).'

The infantry is a different arm to the anti-aircraft regiment. At the school, they tried their very best to break us. Here's an example: 'Corporal Nel (on a weekend pass Friday, which begins at 4.30pm) drilled us till 5! We then had to prepare for inspection because our corporal climbed through an open window before 4.30pm and tipped all our inspection beds and so we had to start from scratch again. At 6.15 we stood the inspection, he rucked every bed and said we were standing inspection at 6.45pm. We stood that inspection too, when he rucked all the beds too. He said that we were now standing inspection at 7.45 with our step-outs ironed (now creased from wearing them for one inspection) and our browns ironed, which we had to put on. Remember too that our beds must be ironed and square and the floor must be polished. By a superhuman effort I managed to do both mine and the guy who sleeps next to me, who had casually pushed off! At 7.45 he told us we were standing inspection at 09h00 on Saturday. Remember, we are still on weekend pass. If he was found out he would lose his stripes. Everyone hates him. There is also a spy in the bungalow.'

But we refused to be broken. By the end of the year, just before our passing our parade, in the last week, they tried everything they could to break us, and we just refused to be broken.

We did everything perfectly, in double time, so fit that no physical demand could not be met. And then, we realised, ironically, amongst ourselves, that they had achieved their aim, and we had actually defeated ourselves.

We were now Apartheid's Soldiers.

It began with an all-out assault on us physically. We were drilled mercilessly in the heat of the day. We ran all day long, up and down hills, around trees, bushes, anything that was about 100-200 yards away. In the middle of a lesson in the stifling dry heat, suddenly the command would be shouted: 'Die klein bossie, links om!' (the small bush, left around it!) and we would leap up with our rifles, running. The standards were very high and we knew we had to meet them. And if we slacked, the entire section would be punished for the sins of one person. This was a way of bonding the section, and also ensured we helped each other, or 'bliksemed' (beat) each other to achieve what needed to be achieved with the minimum of pain.

Inspections were tough. The first inspections we were more or less used to, although we worked harder to be neater. We polished the floors until they shone, using 'taxis' (sections of blanket rather than shoes) that continued to polish the floors. Wearing of shoes or boots were forbidden in the bungalow. I learned how to iron razor-sharp creases in my pants and shirt sleeves (despite the irony that the 'browns' we wore were designed to not show up on infra-red at night, but did so once they had been ironed).

Then came the first inspection by 'the lieutenant', our platoon commander, whom we had only seen once before. He was a mystery, a powerful and dangerous man. He would arrive at the bungalow after we had worked all night to prepare for the inspection. At the appointed time, the corporal shouted: 'Aaan-dag!' (Attennnn-shun!) and we snapped our heels as one to the lino floor, rigid and looking straight ahead. The corporal saluted and the lieutenant entered the bungalow.

Then it began. There was an almighty crash as the first bed was heaved over. The rifle and cutlery of the first man at the door clattered to the floor. There was another crash as his 'kas' was ripped over onto its side. We quaked but looked straight ahead.

Then another almighty crash as the second bed was tossed head over heels. Another kas crashed over. We gritted our teeth. This was ugly. Very ugly. It was total destruction. And so it went on, with every single bed and kas in the bungalow. It looked like a tornado had been through the building.

'Volgende inspeksie in twee uur!' snapped the lieutenant, and stormed out. Fuck! We were stunned. We had spent the entire night working our asses off to do the best we could, and here we had to do better in just two hours! Amazingly enough, it WAS better, and this time the lieutenant was more lenient, only picking out the worst 'offenders'.

It was a very effective shock tactic, and one I used later on both intakes of rookies I trained as an infantry platoon commander. I would not see them for the first two weeks, allowing the corporal to do all the work, and building up this expectation that one day 'the lieutenant' would come and then all hell would break loose.

I realised it was better to be really hard on them in the beginning, and ease up later, than to be easy on them in the beginning and have to be tough later. It was also a way to ensure the respect for the rank was upheld, both by the corporal and the troops. The army rules by fear, and the path of least resistance. Everything is geared around fear and hope. Hurry up and wait.

So, between all the learning we had to do, we were evaluated constantly by our platoon corporal and lieutenant. We were watched like hawks as we learned to shoot, to drill, the administrative duties we needed to learn, map-reading, radio communications, weapons training, roadblocks, conventional warfare, irregular warfare, and so on and so on. It was very intensive, and so was the physical side of it.

24 March to 22 August was the Basic Instructor's Course, where we learned how to train others by being proficient ourselves. I got 6.3 out of 9 for the course, with 'Good' for responsibility, trustworthiness, personality, fitness, morale, discipline, neatness, hygiene, practical aptitude and general knowledge, and average for instructional ability, job ability, managerial ability, perseverance, self confidence, positive aggressiveness and initiative. I was earmarked as a Candidate Officer.

On 22 June, I wrote: 'In the progress tests I always come within the top five guys, and I scored nearly the highest in drill, because no-one has yet scored 70%. It's actually stupid, because the best never score more than 69% and the worst never less than 60% (pass mark) when actually there is a 30% difference at least between the best and the worst.'

For my weapons tests I got 49 out of 50 possible points and 94% for field craft and map-reading theory. I could strip an R1 rifle in eight seconds and reassemble it in 12. I could strip an Uzi submachine gun in 15 seconds and assemble it in 20 seconds.

On 3 June 1975, I achieved sharp-shooter status, entitling me to wear a FN rifle 'flash' or 'balkie' on my step-out uniform. 'I scored 228/250 (91%) compared with 66% last time. My score was the second highest out of 100 guys (highest was 233). Black Balkie is 176. Silver is 212. Full house is a 250/250. Platoon average was 179.2,' I wrote. 'I've seen a R1 with a sniperscope, silencer and armstrap on, and my fingers itched to use it.'

On 11 June I wrote: 'We practiced fire control orders, firing at targets placed in the veld amongst the bush at ranges up to 400m, or even 500m and 600m. It was much more realistic than on the bona fide range. We each individually had to give a fore control order indicating the target properly. On the command 'fire' there is an explosion of rapid and concentrated fire on the target, which generally disintegrates in a cloud of dust, flying chips of rock, sticks and leaves!!!!'

On my weekly Progress Tests, I achieved an average of about 75%, and my speed for running the 2.5km fitness test improved dramatically from 11 minutes to nine minutes. You ran this standard fitness test wearing boots, long brown pants, combat webbing, T-shirt with your rifle and steel helmet.

Once we were drilling in squads on the parade ground, and we saw an Eskom electrician electrocuted as he worked on a power line next to the parade ground. We were not allowed to break ranks to go and help him.

On 29 June, we learned we had to fill in Security Clearance Forms. I told my parents: 'Need family tree and matric certificate. Need names and addresses of relatives, friends etc, so that the Security Police can discreetly check up on our background etc. All very mysterious!!'

This was to haunt me for years. I was naieve, and filled in that my parents were members of (Beyers Naude's) the Christian Institute and founder members of the Progressive Party. You can imagine how that raised eyebrows in the fascist backrooms of SADF military intelligence. This was the reason that despite my good marks, I was only made a Candidate Officer, and was never allowed to enter the Operational Area on the border. I was deemed a security risk.

During our winter, in the regimental phase, we were learning about conventional warfare. We had to spend two weeks, I think it was, in a training area in the Swartberg mountains (Black Mountains). It was mid-winter. In a letter home I wrote when we got back: 'Well, how wonderful civilization is!!! . . . We left at 5am . . . it was cold and snow lay on the (Swartberg) mountains. It was raining too. Our little tents were little rivers, our notebooks got wet, our ink ran and – needless to say, we got wet. We were also doing the basics of what to do when you draw fire. Hitting a wet deck when you are cold, miserable and stiff is a very, how shall I say, dampening experience? Monday night was freezing and fresh snow fell and on Tuesday the temperature was -8 degrees celcius. Cold hey? Then we learned hand signals and section formations, then how to give orders, and the SUN CAME OUT!! Next we had to do more defensive stuff, such as digging trenches!!!!'

When we arrived, we had to dig slit trenches in what was frozen shale. We had to wash our faces and shave every single morning with freezing cold water, and face inspection with our rifles spotless too. Then we would have to camouflage ourselves with grease paint, and branches torn from the Karroo shrubs round about us. And then we would train, mostly 'Vuur en Beweging' (fire & movement).

This exercise trains one for advancing on an enemy under fire. You work in pairs. While one of you fires at the enemy the other jumps up, dashes forward 5-10m and dives on the ground and begins firing. As soon as your buddy begins firing, you jump up, run forward 5-10m and dive down. And so on ad infinitum! Of course there was no reward of overrunning the enemy, taking prisoners or winning the battle. The corporals were relentless.

We called it Aeroplane PT. The corporals used whistles. One blast, we would all dive down. Another blast, we would get up and run. And so it went on until you were beyond exhaustion. We had to cook our own food. We got one litre of water per day. At night, there would be periodic explosions as the corporals and sergeants would wander around throwing thunderflashes, to simulate shelling, sending flares up into the sky, illuminating the veld with a curious greeny-magenta colour. Sometimes machine gun fire would crack overhead. It was impossible to sleep. It was not called Operation Min Slaap for nothing. Sometimes they used loudspeakers to impose psychological warfare on us.

'They use propaganda, such as distorted pop music, sound of a crying baby, and voices of propaganda. We sit in trenches with the glare of spotlights, arc lights and the blare of loudspeakers for about a week. Speed march every day for about 3km in half an hour. We are the best trained troops in the country at the moment,' I wrote exhaustedly.

Or we would be forced on a route march at night, marching 20-30km and returning to our slit-trenches exhausted, only to have to wash the greasepaint from our faces for the next inspection. Some nights there were unnerving sounds in the bush. It sounded like someone was having their throat slit. We didn't know if it was wild beasts like leopard or hyena. We later discovered, rather mirthlessly, that it was honking donkeys!

Nearly all of us got sick, doing constant fire & movement in the slush and snow. When we got back to base, I was so sick that the corporal told me to go and report sick. I refused because then one became known as a malingerer. The lieutenant came and gave me a direct order to go and report sick. Unwillingly, I went and sat in the queue. The doc examined me, and said: 'Look, there's little I can do now. You're recovering from pneumonia. You'll be OK.'

I wrote home to my family: 'Did you know that in a linear night attack in conventional warfare the front troops walk through a minefield to the objective? Good grief.' I also learned the Russian words for Mines, TNT and explosive!

There was another map-reading exercise we did, called Operation Vasbyt 5'. Our sections each had to use our maps and sets of co-ordinates to cross the Outeniqua Mountain Range in a five-day exercise. Of course the rendezvous (RV) were all either at the top or bottom of a mountain, and we went from one to the other. We got ready before the march began, buying in chocolate, Pronutro, sweets, extra cigarettes and so on. Pre-dawn on the appointed Monday, we left the camp. About two kilometres out, we hit a corporal-led roadblock. They searched our kit and confiscated everything that was not standard issue, including cigarettes. We were devastated. They had just saved themselves hundreds of canteen rands!

It was a tough first day. We had one water bottle each, holding one litre. Our section, radio-coded Whiskey Five' marched about 40km to the first RV and arrived there at dusk, tired, dusty and sore under my leadership for that day. It really tested us, because we couldn't see the RV until 100 metres away, and everyone thought we were lost, and morale in the group was low. At 6.30pm we got to the RV, where an old Bedford truck was filled with all the food. Hundreds of silver tins, all with the labels torn off. No-one knew what they were getting. We were a section of 12 men, as I recall. We got six tins and a litre of water each.

We opened each tin at our bivouac, each tin opened with a bayonet (no openers supplied) and then the contents carefully shared out between all of us. The first tin was baked beans. We joked about the farts to follow the next day, and who should lead and who should follow. Gallows humour.

The next tin was beetroot. So was the next one. And the next one. And the next. Of the six tins, four were beetroot, one was baked beans, one was meatballs. And so it went on, day after day. In the mornings we would climb a mountain, check in at a rendezvous, and then descend again to another RV. One night we spent high up on a mountain, just the grass and us on the crest, and the wind whistling coldly around us.

The following morning we began to descend. At one point we slid on our butts down a 30-40m slope, using our rifles as oars to maintain balance. At the foot of that descent, we found a beautiful mountain stream, where the water ran red, cold and clear. This was probably the best water I have ever drunk.

We slaked our thirsts, filled our water bottles and moved on down to the plains below. We began to move through the pine forests, fighting and cutting our way through thick, springy ferns, down to farmland towards the coastal RV at Victoria Bay. We tramped along farmlands where we plucked raw potatoes from the fields and ate them. No washing or cleaning, just rub off the dirt and eat. We were starving.

We finally made it to the Herholdt's Bay RV, where we were welcomed by the RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major and our corporals and lieutenants. There was a huge braai laid on for us, but our stomachs had shrunk. Nevertheless, I ate eight doorsteps of bread and butter, one steak, 3 chops, 3 boerewors, 2 potatoes, 2 tomatoes, 1 firebucket (= 3 cups) of milk and two beers.

We slept on the beach, and the next day rode Bedfords back to Oudtshoorn. Lying on top of all the equipment, I found it easy to sleep. I could sleep anywhere, in any form of discomfort, and we were really, really tired.

'Our syndicate came first! 'Whiskey Five won!' Now we are gorging ourselves on water, bully beef, condensed milk (neat!) sweets, milk, fruit and wholesome good food!!!!' I wrote elatedly to my parents.

When we reached camp there was more bad news. C Branch, which had done a similar expedition over the Swartberg Mountains had lost two men to drowning. They had tried to make a raft to swim over a lake rather than take the very long way around, and the dark freezing water had claimed them. Lives of National Servicemen were cheap. We were expendable. 'War is a good business: invest your son', goes the old adage.

During the platoon weapons phase, we learned how to use flamethrowers, Strim rifle grenades, hand grenades, 9mm Star pistols, 9mm Uzi submachine guns, Bazookas, and Bren Light Machine Guns. We also had some experience with Entac anti-tank missiles, 60 and 81mm mortars, Vickers machine guns, followed by a course on section leading.

I remember another incident. We were lined up outside the company HQ, and Captain 'Blackie' Swart came out. He was our company commander, and we were all in fear of him. He was Permanent Force, a shortish, very fit soldier with a very tanned skin and black hair. His chin showed his determination.

Some of us were singled out and ordered to step forward. I was one of the names. There were probably about 10-15 of us. We were going to do pole PT with the captain. This would be ugly.

Pole PT is a unique torture. Two of you have to shoulder a telephone pole. The pole is too wide to sit neatly between your shoulder bone and your neck, so it rubs constantly on that raised bone in your shoulder. There is only one way to lessen the discomfort, and that is to run in step with each other. The end result, ALWAYS, is that your shoulder is rubbed raw, and afterwards, your back aches from the unequal distribution of the weight of the pole.

So off we went with the captain shouting. He was dressed in his browns and a T-shirt. We wore our full battle kit (webbing, rifle, helmet, and browns. I can't remember the drills we went through, the exercises and the pain. What I do remember is puking repeatedly while he goaded me on. I also remember actually passing out, then coming to, with him looming over me, shouting like a demented demon. I was hallucinating. The place where we were looked like something out of that painting by Breughel entitled 'The Triumph of Death' (1562). It was a dark hell that day, but I survived. I discovered reserves I never knew I had, and a determination to not let this bastard get me down.

Breugel's 'The Triumph of Death' which was similar to my experience of excessive PT, which made me pass out, hallucinate and puke my guts out as a sadistic captain goaded us on.

From 8 September until 24 October, I did Platoon Commanders: Operational course, passing 2nd class. From 27 October until 12 December it was Platoon Commanders: Counter-Insurgency Operations, which I also passed 2nd class.

The Coin Ops, as Counter Insurgency Operations was called, was the toughest course of all. By this time we were super fit, and looking forward to graduating after all our hard work. Coin Ops was also the most pertinent to our training, because this was the war being fought on our borders. The Bush War was a very low intensity war at that time (mid-to late 1975). I enjoyed learning bushcraft, and what they called 'boslaan' (bush lane shooting, where you are surprised when a target jumps up and you have to shoot it with two 'taps'). The first shot, or tap, is usually deliberately low, to see where the bullet goes, and the second to correct your aim. You don't aim properly, you walk with your rifle at your shoulder, pointing down, and your hand holding the barrel part with the finger pointing the same direction as the barrel. The theory is that when you point, you point DIRECTLY at whatever it is with your left hand. So, in the same way, if you 'point' with your finger at the enemy and fire, you will be quite accurate. This improves the speed of a soldier's reaction time in combat, and should improve the kill rate. So we practiced continually.

After all the theory, we finally went to do our practical in the bush training area about 20-30km from the camp, in the foothills of the Swartberg. It was centred around a dense bushy place ominously called Luiperd's Kloof (Leopard's Ravine).

One of the things we had learned was to call in close air support by radio (for instance if pinned down under enemy fire). So one day, we lay at the edge of a dam, imagining the enemy was behind the dam wall and pinning us down. We had to call in air support from the SA Air Force, which had sent down a flight of Impala aircraft especially for this training exercise. So we called them in on the radio. We tossed the smoke grenades to denote the FLOT (Front Line of Troops, a green grenade on the right and a red one on the left). But nothing could prepare us for what happened next.

Our world exploded. The dam wall disintegrated into chunks of soil that rained down on our heads. We tried to dig ourselves into the earth with our elbows and covered our helmets with our hands. There was dust and smoke everywhere. Then the sound hit us like a stone wall. The noise was unbelievable. First the angry chatter of machine guns and exploding rounds, and then the roar of the jets as they pulled up steeply over the dam wall and peeled away for a second gun-run. The earth shook, and we wished we had not been born. I can't imagine what it must be like to be on the receiving end of this. It was really terrifying, and these were OUR guys shooting at OUR targets! Unforgettable experience. Imagine what it would be like with Mirages.

We also had to jump out of Puma helicopters while they were still in the air. They would come in low over the veld and at about a height of 5-10 metres we would leap from the chopper (or be thrown out by the Staff!) to land uncomfortably below. The first time I did it I had a heavy radio on my back that klapped my face deep into the dirt as I landed. Then we would get picked up again, the wash of the rotors churning up dust as we ran to the chopper and were pulled inside as the gunship began lifting off. It was exciting.

It was at the end of the course, and a long weekend was coming up. We were all planning to go to Cape Town when we got back to camp. But there was a nasty surprise waiting.

Our key instructor was a Staff Sergeant. He was a tall man, well built, and all muscle. He didn't look like a Superman, but he could tuck an R1 rifle upside-down under his armpit and with one hand, on automatic, use the 20 rounds in the magazine to cut down a tree at 50 yards. Anyone who has ever fired a R1 knows this is absolutely awesome. His hand, when he clasped his tobacco pouch, pipe, and matches in one hand, left only a tiny bit of the pipe showing at each side of his hand. He had a handlebar moustache, and was a former Recce.

Recces were the most elite unit, and they worked in groups of five specialists (usually explosives, medic, communications, and other specialities). They were all parabats, and would be parachuted in deep behind enemy lines at night to carry out sabotage and other specialised tasks. Most of them had that 1000-yard totally emotionless stare that speaks only of trauma witnessed.

So our Staff was one of Them. As we emerged from the bush for the final RV at Luiperd's Kloof, we found him standing on the back of an open Bedford truck, leaning on his rifle and smoking his pipe. We gathered in front of him and sat down. His lecture began thus: 'I told you not to walk on the roads, but you walked on the roads.' He described a tree to us at the top of the kloof, about 500m away up a steep hill and told us to run. When we came back, he had another instance of us disobeying his rules.

So we ran again. And again. And again. All afternoon. And this was with full battle kit, full pack, because we had been in the bush for two weeks without washing. Whenever we slacked off up the hill, in his opinion, or got tired, he would pick up his rifle, and pop off a couple of 'taps' at our heels. There is nothing like a rock exploding next to you as a 7.62mm hard point bullet hits it to make you pick up your feet and realise that life could be short. You discover reserves you never thought you had!

Finally, at about 5pm, we gathered again, exhausted and sweating, in front of the Bedford. Staff looked at us contemptuously. 'Those of you who can make it back to camp before 7pm can go on weekend.' With that, he dropped to the ground with his rifle, unhooked the tailgate of the truck and dropped it to reveal a Bedford stacked with poles. Our hearts sank.

We took our poles, this time putting the pole behind our necks and running two abreast, with the pole seated between our helmets and our backpacks. And so we began the long lonely dirt road back to camp. Staff roared past us in his open cut-off Landrover and disappeared in the dust, as sunset approached and we ran, perfectly in step, with our heads down, to camp.

The only way to do this is to not look at the distance to be covered. You look at your feet, run in step and get into a hypnotic rhythm that carries you along forever. The fittest of us made it back before seven, and quickly showered and changed into civvy clothes before hitting the road outside camp. Those who didn't make it by the deadline spent a lonely weekend in camp.

It was on another weekend pass that I was getting a lift to PE with some other soldiers who had a car. We had just finished a 'Buddy Aid' course the week before (I got 81%), learning how to deal with gunshot wounds and watching 16mm films from war zones such as WW II, Korea and Vietnam. Seeing as we had left camp in Oudtshoorn after 5pm, it was dark for most of our journey.

On a lonely stretch of road outside Uniondale, we came across a bizarre scene. A car was parked on the opposite side of the road, on the gravel verge, and a man was lying near the front wheel. Another man was kneeling over him. We screeched to a stop, and ran over to see what had happened.

The man on the ground was lying very still, but was alive. Blood was coming out of his mouth, nose, eyes and ears. I saw a pistol lying on the ground near him. Armed with our fresh knowledge, I wanted to give him mouth to mouth immediately, and one of the other soldiers began heart massage, pumping on his chest. I put my hands behind his head to turn his head to the side so I could clear his mouth and air passage. All I could feel was splinters of bone and the soft tissue of brain. He had been shot through the mouth. I knew there was nothing we could do to save his life.

His companion was beside himself, hysterical. Then I heard the sound of a pistol being cocked. We turned around to see the injured man's companion waving the gun around. One of us lunged up and grabbed his wrist with both hands. I kicked the gun out of his hand and with that, the man collapsed, weeping hysterically. We went back to the injured man, but as we tended him, I heard the death rattle as the last air in his lungs escaped through the bubbles of blood in his throat. He was gone. My first look at a dead man.

There were no cell phones in those days, so we had to wait until someone else who had stopped called the police and ambulance. It took forever, but we stayed there, trying to keep the survivor calm and warm, and we put a blanket over the dead man. Had it been murder, or was it suicide? We'll never know. We left our details as the first witnesses on the scene, but never heard about it again. It was after midnight when I arrived in PE, still with blood on my hands and clothes.

When I look back, my 'too honest' security questionnaire was perhaps responsible for some of the harassment I received at the Infantry School from senior officers. Second, when we 'klaared out' (cleared out) at the end of our courses, everyone became either a Corporal or a Second Lieutenant (one pip) according to their marks. I was one of small handful of seven designated 'Candidate Officers' (COs) for some unspecified reason. COs were not really respected as much as 'Lieuties', and did not have to be saluted.

We were told it was an 'administrative delay' (one that went on SIX MONTHS!) and only came through because of sustained pressure by my parents and uncle. My father had been a major in WW II and my uncle a lieutenant. By February, five of the other CO's had been cleared but mine continued to be delayed. It finally came through on July 1. A reason was never given, and I was not allowed to do border duty for 'security reasons'. Apparently I might have gained information to give to the 'Communists' of the Christian Institute, like Beyers Naude!

It was bitterly disappointing for me not to go to the border. Everyone wanted to go and experience it. Yes, we were young and naieve kids who didn't actually understand what war was REALLY about.

I had been transferred to 7 SA Infantry Battalion at Bourke's Luck and had trained an intake already before my clearance came through. A signalman alerted me one weekend as the signal had come through the telex on a Friday night. I went up to the signal room, took the telex to another room, and copied it word for word, as I didn't understand all of it. But I was really elated that, FINALLY, I would get my pips, and everyone would have to salute me. I felt I had been cheated and humiliated by the apartheid army.

Looking back, I can only be pleased that I never had to kill anyone, that I never experienced the trauma of a 'contact' with 'the enemy' and that I was never wounded or killed myself. I was one of the lucky ones, despite having suffered the trauma of training for an elite unit.

Just before we 'klaared out' of the Infantry School, news broke that SA had invaded Angola. The 'quiet war' was over. It was now a 'hot war' with tanks, aerial dogfights between Russian MIGs and SA Mirage fighters, bombing, and conventional warfare. SA advanced right to the outskirts of Luanda, we heard that they had actually entered it.

A Company from the Infantry School was designated to go up and join the fight. We were very disappointed when C Company was chosen rather than our B Company. We all wanted to fight.

But another alarming issue had arisen. When I had joined up for two years, the service period was only one year, and it was going to be made two years soon. But in this transition period, you could sign up for two years and get a bonus of R3000, which was going to pay for my first year university fees. My parents were unable to afford more than one year's fees, so my plan was to pay my own first year, they would pay the second year, and I would get a student loan for the third year.

But now that the 'quiet war' had suddenly exploded into a hot one, the political ramifications as well as the danger factors escalated considerably. I no longer felt comfortable in uniform (perhaps those security chaps had been right about my Security Clearance after all!). I didn't want to be seen fighting actively in defence of apartheid. National Service was one of five options: the other four being going into the police, to university to delay the day, going into exile, or going to jail for six years. I didn't want to go into exile, and I didn't have the money for university. I didn't fancy six years in jail.

These were before the days before the End Conscription Campaign, so there was no support for conscientious objectors, and we knew that Jehovah's Witnesses went to jail and had a really tough time. I was on the horns of a dilemma, and I was only halfway through my conscription period.

The Reluctant Fighter (1976) 7 SAI (Bourke's Luck) & 4 SAI (Middelburg)

But a tragedy happened at Bourke's Luck. One of my platoon was a promising young man with freckles and straw-coloured hair. Mitchell was his name. He was one of the achievers, an exceptional young man with a good attitude and showing good leadership skills. But Bourke's Luck could get very very hot in the summer, with temperatures in the 40s (Centigrade!) After one particular training session on a Friday afternoon, Mitchell did not look well.

I told him to go and report sick, but he refused (just as I had done in Oudtshoorn, he was afraid of being labelled a malingerer). He was looking flushed and I suspected heat exhaustion. I gave him a direct order to go up to the sickbay, and, unwillingly, he went. He came back and said the medics said there was nothing wrong. I told him to go up and get the medics to call a doctor to attend to him and sent another troopie up with him with my explicit instructions. I was about to go on weekend home, so after making sure he went to the sickbay and was admitted, I went home with my buddies, who were all lieutenants or corporals. One had a car and we got lifts together.

When we came back on the Sunday night, I was shocked to find that Mitchell was dead. The doctor had not been called by the medics as per my instructions and he had suffered heat exhaustion, which turned into fatal dehydration.

The hardest thing I had to do was write a letter to his father. It was awful. I had to make an affidavit about it, and there was an investigation, but as far as I know, nothing came of it. Just another sacrifice for the apartheid regime.

I gritted my teeth and carried on. But worse was to come. I trained my first intake of national servicemen (NSMs) and they departed for the border. Some of us were then transferred to 4 SA Infantry Battalion (4 SAI) in Middelburg (Transvaal, as it was then known) to train another intake. By now it was July, freezing cold and Middelburg one of the coldest places in South Africa. I hate the cold, so it really bit me. Once again I used the 'first inspection technique' to create fear and terror in my recruits.

At least Middelburg was closer to home, so we shaved off at least two hours of our weekend travel times. Things were calmer again after the withdrawal from Angola, but there was still fighting. But, in June 1976, Soweto exploded with the student riots. Within days it had spread all over the country.

We were placed on immediate standby. I had 150 men under my command at that time, and the Bedford trucks were lined up in the road outside our bungalows. The troops were in full combat gear, and we had live ammunition issued to us, as well as tear gas and smoke grenades.

We drilled all day, doing D-formation drills (a formation for crowd control) and the rapid deployment of troops from moving trucks (you learn how to run and jump off the back of a moving Bedford, with your own momentum cancelling out the movement of the truck, so you land on your feet, rifle at the ready for instant action, just 10 metres from your nearest buddy). At night we dozed in our kit, in rows in front of our bungalows, waiting for the call from the police.

I was beside myself with anxiety. There was no way I was going to go into the townships and order my men to shoot down kids protesting against an unequal education in a foreign language to them. I was on their side, and now I was caught in the middle.

I resolved that if the call came, I would immediately go to my commanding officer, a captain, and tell him I was not prepared to go into the townships for political reasons. I would be arrested and tried. Treason? Failure to comply with a lawful order? Would I be court martailled? Would I go to jail? Would I face a firing squad? All these thoughts and many more raced through my head for the three or four days we were on immediate standby. Finally, we were stood down, to my great, but secret, relief.

It was at this point that I realised I had to make a decision about which side I was on. I was already on the wrong side. The horns of a dilemma. Getting out of it would mean jail time for sure. I had six months left. I decided to try and just stick it out and keep out of any action.

After the intake was trained in basics, they departed for the border, and our group of corporals and lieutenants went back to 7 SAI at Bourke's Luck. I applied to go to 1 Military Hospital for speech therapy for my stutter, and to my surprise, I was accepted. It would keep me out of action for some weeks. I was to spend three weeks there, seeing a psychologist. Being a lieutenant by now, I had my own room just off the ward. It was in September 1976.

I was in Ward 22 or 24, where the infamous 'Dr Shock', Aubrey Levine experimented on gays, using unethical aversion and shock therapies, sexual abuse and other unprofessional techniques, such as the administration of truth drugs and other forms of 'therapy' that were an abuse of human rights.

I learned relaxation techniques and had interviews with a psychologist (a Major), and was fortunate not to experience any unprofessional conduct myself or to meet Levine face to face.

My interactions with the patients were interesting. Some of them were genuinely disturbed psychologically and had mental disorders. Some were normal gays, sent there by a hostile military regime, and many of them were drug users or alcoholics. Some had post-traumatic stress disorder, although it was not known as a medical condition at the time, it was just known as having gone 'bossies' (gone bush-mad). But mainly they were harmless kids, jailed in this place for being different, for being outlaws of various kinds, or rebels.

I thought 90% of them were normal kids like me, who didn't fit in with the fascist military regime. Some were heavily drugged all the time. Many had been to a secret military punishment camp called Greefswald, on a farm in the northern Transvaal near the confluence of the Shashi and Limpopo rivers on the Zimbabwean border. People who smoked dope would be sent there.

This was, by all accounts, a very brutal camp, with hard labour de rigeur and some reported deaths or later suicides. Levin later managed to get into Canada and practiced there until he was uncovered after he tried to sexually abuse a Canadian out on parole and was arrested. His history as an apartheid military doctor then came out and he was jailed for five years at the age of 73 and stripped of his doctor's licence.

But we had some pretty tough days at 7 SAI. I remember the first time we were jaaged up Majuba Hill, which overlooked the camp from across the main road. It didn't look like a very imposing mountain until you began to run up it.

Majuba, the hill on the left, photographed in 2007 from the national road. In 1976 there was no settlement on its slopes.

Once again it was the National Servicemen NCOs and officers who were taken up it by the Permanent Force bullies and psychopaths. Near the top, one actually had to CLIMB. So it wasn't just PT for us, it was serious physical work. Of course on the way down, being a steep hill, one's shins took a lot of punishment and they ached for days afterwards.

It was about 3.30pm. We were told if we made it back to camp in two hours, we could go on weekend.

So we shouldered our loads and began to run. The landrover disappeared in a cloud of dust round the bend. It reminded me of Luiperd's Kloof and the Staff.

The bridge at Pilgrims' Rest, where we were offloaded with the poles. The road was dirt then.

We'd run about 100 yards when we crossed a bridge. One of the teams stopped and a lieutenant said: 'Look, the river's in flood! This goes right down to the camp. We don't have to run! We can ride the poles down to the rapids and get out just below the camp!' He was right! It took us about 30 seconds to toss our poles into the river and dive in with them, boots and all. The water was cool and refreshing as it swept us along, over little rapids, small knots of stones and through deeper, quieter water. It didn't take long at all for us hear the roaring of the rapids ahead.

We got out at a weir, and walked up the embankment to the main road. We formed ourselves into a squad with our poles, and, dripping, marched up in double quick time to the camp entrance, where an open-mouthed troopie saluted us as we passed. We ran down to the company barracks, dumped the poles neatly in their slots, formed up another squad, watched curiously and in awe by our troopies, who could not believe our spirit and discipline, nor the fact that we were dripping wet.

We marched up to the officers' quarters in a squad, jumped into the showers, changed into our civvies, and strolled casually into the Mess bar for a drink before hitting the road to Pretoria and Johannesburg.

Our company commander was sitting there with our sergeant major. Their jaws dropped to the floor. We were about an hour and a half early, and we looked cool and refreshed, not hot and bothered. We ignored them, walked to the bar, ordered cool drinks with ice, and downed them. Then we left.

There was nothing they could do, because we, as leaders, had exercised our initiative to overcome a problem and this was what was expected of us.

Part of the training required some night work with the troops we were training. Map reading, star-reading, moving quietly at night, and so on. So we began with that. The terrifying thing about being a leader is that you have to LEAD. Be in front. Take charge. Control your own emotions and help others.

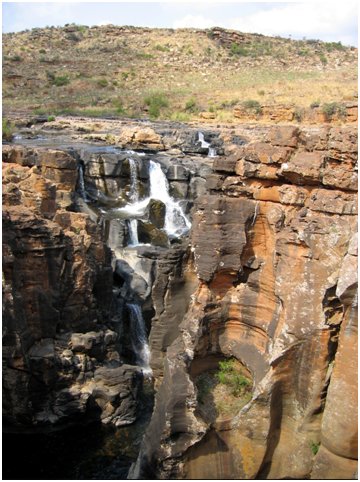

So there we were, standing at the edge of the Blyde River, sometime around midnight, no moon, just the rushing dark waters and a couple of waterfalls and slippery rocks. This was my platoon, and it was my duty to lead them over this river. Nature never seems so fearsome as it does at night.

The Blyde River crossing I had to make at night.

Well, after that, I guess I had conquered my own fear of these raging waters. My feet were soaked, but my heart was strong. My spirit high. I had done it. We went on, later crossing the river again, and then walking along the edge of a steep cliff with real raging water below at the potholes, as we moved to an area for the map-reading exercise, filled with holes and gullies that ambushed us as we walked with our maps, peering at our compasses, staring at the stars, and falling into holes. A night of horrors.

At least the 2.4 km fitness test held no fears for me. I was the best at it. It was at Bourke's Luck that I ran it in 9 minutes dead, with helmet, rifle, boots and browns, and webbing. I took the record at that time, and was proud of it.

But other dangers lay on the horizon. We had completed our training of the troops in Coin-Ops, and were to deploy to the bushveld for two weeks training. The night before we were to go, the company sergeant-major and the PF lieutenant managed to get several of us NSM officers very very drunk on a combination of vodka, brandy and coke, rum, and who knows what else? I don't remember much.

The next day, early, the Bedfords were lined up for us and we boarded, me in the cab with the driver in the front Bedford. I had a humungous hangover, and had been sick most of the night. The fumes and heat rising from the Bedford's gearbox and engine between the seats was nauseating.

The convoy had to stop twice on the way to the Timbavati to allow me to get off the truck and be sick in the bushes. It was very humiliating, and I'm sure the PFs had a good laugh about it. We were 'Engelse soutpiele' (English salt penises) and they were good ol' Boere.

B Coy barracks at the bottom of the camp.

Finally we arrived in Timbavati, famous for its white lions, a private game reserve that adjoined Kruger National Park. We were here to patrol it for two weeks as part of our practical training in bush warfare.

We spent a lot of time walking in the bush, unarmed. I think each of us platoon commanders had five live rounds in case of real emergencies, but really, we were patrolling unarmed amidst the Big Five. Our own fears were probably the worst enemy we faced, but just for good measure, we did one night lay an ambush, and were all sitting quietly in our positions when a leopard sprang up into a tree behind us, and began panting in a sort of sawing sound. To us this indicated hunger.

I climbed on the radio to Coy HQ and asked in a whisper if we could move the ambush down the pathway about 200m. They agreed. We all, very quietly, got up, and slowly moved down the pathway and away from the leopard. One just wonders what the leopard was thinking?

Every night, we would have to bivouac down. We would make little shelters for ourselves out of dry thorn branches, and crawl into them and pull our webbing in at our feet to make our sleeping place impregnable. Well, sort of. Often we would awake in the morning, the guards having seen nothing at all, to find that hyenas had pulled our webbing away and chewed through it, or half-eaten our dixies or boot polish. This was pretty stressful stuff. Then we would have to patrol, walking through long elephant grass, and hearing all sorts of sounds ahead of us in the long impenetrable grass, fully expecting a lioness on the rampage to come bursting through, or a 'dagga boy' old buffalo wanting to swing us on one of his horns.

But near the end of the two weeks, we did some chopper drills with Puma helicopters. These pilots had seen service in Soweto during the 1976 student riots, and they had some stories to tell around the campfire at night, with the cicadas going mad in the bush, hyenas yelping and lions calling in the night.

In the flickering fire light, I heard how the floors of the choppers were filled with empty cartridge cases as police commanders fired 9mm pistols randomly down on students and protesting Sowetans. These stories were later collaborated by eyewitness accounts on the ground.

I also heard stories about how, up on the border with Namibia and in Angola, senior politicians and top-ranking police and army officers would shoot rhinos and elephant herds down with gunship machine guns, and then land to cut off the rhino horns and elephant tusks with chainsaws to transport back to SA in military trucks and into international smuggling routes to help pay for SA-supported Jonas Savimbi's and Unita's civil war against the ruling MPLA socialists in Angola.

Sure there was probably too much brandy and coke Klipdrifting around, but these stories were later collaborated by other servicemen and media reports in a tightly controlled media environment in South Africa. While I was at university, some of these stories began to surface, and they were totally believable because I had heard first hand, deep in the African bush, with dancing firelight, the truth that comes from loose talk and bradaggio.

On our last day in Timbavati, the NSM officers in our battalion were taken to the bank of a river. We sat on the bank of this dry sandy watercourse, and were briefed by a senior PF officer (I think it was a colonel or a lieutenant-general) about the communist threat facing South Africa, and how the banned ANC and SA Communist Party (SACP) were supported by the MPLA and FNLA (Angola) and Frelimo (Mozambique), and the Zanu and Zapu forces in Zimbabwe. It was our task to heroically fight these threats to our country.

We were urged to join our local commandos on 'klaaring out' (demobilisation) and support the fight against black and communist supremacy that was backed by Russia, East Germany and Cuba. It was an impressive diatribe, and I did join the local commando when I arrived at the university that used to be called Rhodes, but I pretty soon got disillusioned with it, took up left-wing student politics and handed back my equipment (including an R1 rifle!)

So, back we went to Bourke's Luck, and finally, happily, after our 40 days of 'vasbyt' (hanging in by one's nails), we shed our browns, left the army and went HOME. Not a moment too soon! I was sick of the army, and apartheid.

Published: 16 May 2020.